Building relationships through letting go of control

Letting go of control.

Existing in relationships triggers everything.

Manulani Aluli Meyer (2008)

What does it mean to exist in relationships in the context of a classroom? One of the first things I was taught during my teacher training is that relationships are key. Up until recently I believed I was doing my best to foster relationships between myself, the students and their whānau. This belief in my abilities to build and develop meaningful relationships was tested when I was accepted as a recipient of the Dr Vince Ham eFellowship with Core Education. Through my research I was forced to re-evaluate what it meant to form relationships, and the work that needed to be done to do this. My eFellow project was structured around this research question:

How can real-time reporting, via Seesaw, support reciprocal/ako relationships between learners, whānau and school?

I had a hunch that through live reporting, whānau, students and I would switch easily between the roles of teacher and learner. I optimistically saw myself collaborating with whānau and students to complete my research. This optimism was quickly dashed by my first whānau focus group discussion, which was attended by one parent. This experience taught me my first lesson – that good intentions and morning greetings are not enough to create the type of strong and trusting relationships I was looking for. I had not taken the time to nurture and grow these relationships, instead I expected whānau to engage in ways that were dictated by me. I expected whānau to engage with me simply because I had good intentions; I had failed to recognise inherent power imbalances.

According to Berrryman, Lawrence and Lamont (2018) to break down power imbalances and build culturally responsive relationships, educators must create spaces in which to first listen to our students and their whānau. Building respectful relationships takes time and commitment. I realised that I needed to create opportunities for whānau to be part of the classroom. I also needed to create opportunities and space for whānau to engage with me. I wanted my research project to build this space and I assumed it already existed. My initial forays into the project showed me that I could not move forward with relationships without first having established them. This realisation led me to organise a cake and reading afternoon with the children and their whānau.

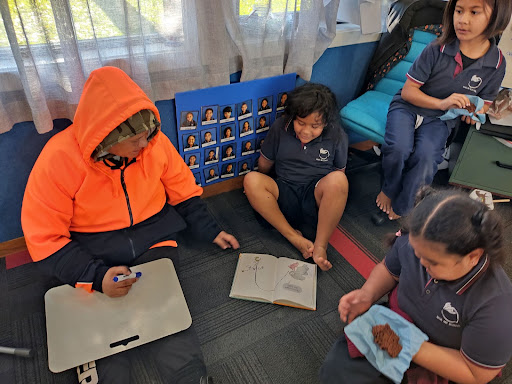

I invited whānau to attend a cake and reading afternoon in the classroom during class time. In preparation the children baked a cake and we practiced two songs – Kina Kina and Si Manu Laititi to sing to the parents. The whānau of six children arrived and the children showed their parents their favourite parts of the classroom and what they had been learning. It was insightful and meaningful for me to watch the children interacting with their whānau. One chose to show how he used Mobilo© to make Beyblades©. Another wanted to show all the artwork they had completed in the classroom and proceeded to walk their family around to see it. I witnessed children choosing their favourite picture book and having their family read it to them. Interestingly the children whose whānau did not attend enjoyed interacting and playing games with the adults that were there. It showed me the value of a wider whānau connection, and how tamariki can connect with the whānau of other students in meaningful and productive ways.

What was different?

The cake and reading day was a success, it was a turning point in my research and my understanding of what it meant to build relationships. But what was different?

- The event was led by whānau and ākonga. Whānau came and went as they pleased, and ākonga led the interactions in the classroom.

- I let go of control. In essence this letting go involved me standing back and allowing the event to unfold, which was not as easy as it sounds. There were many times I wanted to step in, take over, point something out. It also made me feel very vulnerable, open to perceived judgement that I was not doing enough for my students.

The cake and reading day was a pivotal moment for me. It resulted in the beginnings of an embodied understanding of what it means to be in relationship with whānau and ākonga. Relationships cannot be simply a cerebral undertaking; a checklist of steps to be taken to ensure that I ‘know’ the whānau and tamariki that make up my classroom. This research project has shown me that relationships take time and effort. Relationships are not static, they are continually changing and require each person to respond to that change. I am starting to realise that existing in relationships with tamariki and whānau means being uncertain, taking risks, listening, adapting, giving space and letting go of control. There is no handbook for relationship building, rather it requires each person to be present and open to the other—relationship building requires ongoing work.

The e-fellowship experience has enabled me to cultivate a new understanding of what it means to be relationally connected with whānau. This understanding manifested itself in the following ways:

- Waiting in silence for as long as it took each whānau member to read a report before starting a conference:

- Staying on the phone and listening to a parent who was going through a difficult time:

- Working with a parent helper’s timeframe— as opposed to a set schedule from me—so that they can pop in when they are able to:

- Creating opportunities for children to make more choices in the classroom:

- Taking the time to allow conversation to flow rather than launching straight into what I want to say:

- Inviting parents to be part of the class in ways determined by them.

All these examples demonstrate that time is one of the most important aspects embedded within building and maintaining relationships. Each relationship is different and requires constant attention and time. The question is how do I create this time and space, in a current education system that does not value it.

Kirsty Macfarlane's 2021 eFellow's report.

Author

Kirsty Macfarlane

Kirsty Macfarlane is a teacher of Year two ākonga at Nga Iwi Primary in Mangere, Tāmaki Makaurau. She is passionate about pedagogy, social justice, and contributing to an equitable society. Kirsty was a recipient of the Dr Vince Ham 2021 eFellowship. Her project investigated how live reporting is used to challenge how educational systems function to reproduce primarily Pākeha knowledge.

References

Berryman, M., Lawrence, D., & Lamont, R. (2018). Cultural relationships for responsive pedagogy: A bicultural mana ōrite perspective. Set: Research Information for Teachers 3-10

Meyer, M. A. (2008). Indigenous and authentic: Hawaiian epistemology and the triangulation of meaning. Handbook of critical and Indigenous methodologies, 217-232. Thousand Oaks; SAGE Publication.

Explore more content

Explore our wide range of education related podcasts and blogs, ranging from experts discussing Kaupapa Māori, Cultural capability and te reo Māori, Leadership, Pacific viewpoints, Digital and innovation, Inclusive learning and more.