Disruptive educators and quality learning design

Complexity and challenging times

We’ve encountered many new kupu/words/terms recently that describe different approaches to the delivery of learning. Hybrid learning, online, off-site, blended learning, synchronous, asynchronous, remote learning, are just a few. These disruptions come at a significant stage in our national curriculum refresh, as we near our vision for learning in 2025.

I have been fortunate to experience and observe many students, educators and schools during unexpected serious ‘events’: COVID, floods, earthquakes, community losses, and family trauma. In these times the existing systems and strategies that support learning are immediately disrupted, timetables forced to change and adapt, sometimes in an immediate and reactive time frame. These events can cause issues around wellbeing and learning, as well as inclusion, equity and accessibility. In addition, stress, workloads, negative behaviours, pastoral incidents, and group dysfunction can increase.

I’d like to share in this blog my observations about learning design; what happens in our classrooms. How do the effects of ‘disruptive events’, both human and natural, test the robustness and quality of what ākonga (students) experience in the classroom and our pedagogical choices as educators?

Human disruption comes in many forms

An online group of DisruptEd educators, and many ‘disobedient’ educators across Aotearoa, are championing educational disruption. Disobedient disruptors deliberately seek to improve the effect of outdated educational systems and strategies to better meet the needs of ākonga. These educators have much in common with the natural and societal disruptors. They test existing systems, to see that they are fit for purpose in meeting learner needs, now and in the future. This group of educators see beyond the surface of the systems and strategies to the depth of the systems and their impact on our ākonga. This ‘seeing’ leads them to intervene; to become disruptive and disobedient, to make changes, deliberately design intervention pedagogies, take transformational action that questions and begins to shift the systems that surround them to reducing and removing their negative impacts.

They do this quietly and almost invisibly. They almost always demonstrate the instinctive values of empathy and equity, because they know how it feels to be disconnected and excluded. They show humility and passion, and are naturally collaborative, believing that "it takes a village to raise a child". Their lens of equity, inclusion, and awareness, is wide and deep. They focus on relationships they have with colleagues, students, whānau, community, local council and businesses. These networks provide both the guidance for their intervention, and the resources that support it. They also create an invisible 'wellbeing shield' system of teaching and learning within their classrooms, that protects and inspires ākonga and them as educators, from the negative influences outside. They design quality learning that gets into, and more importantly stays in, the hearts and minds of their learners, because they know the greatest tool of change available is their fundamental task of learning design and relationships.

“The design of learning is the fundamental task of teachers – they do it every day, sometimes explicitly as an extension of their planning, but more often it's what happens almost naturally as a result of the structures and systems that exist in most classrooms.” (Wenmoth, 2022)

How quality learning design looks and feels

In almost every case I have observed, these disruptors are experts at the design and delivery of authentic, engaging, and outstanding learning. They also take a huge social risk, as their efforts and solutions can be unwelcome to colleagues and leaders who like the status quo. So often, in spite of the systems that surround and restrict them, they design classroom learning that develops students' creativity, critical thinking, resilience, collaboration, connectedness, empathy, self-awareness, testing bias in themselves and those around them. They knowingly create a barrier from the damaging school systems and external events, by designing fun, engaging, high quality learning. They constantly develop positive, equity focused relationships, and inclusive learning environments. You can feel the uplifting power and energy of these as you enter their classrooms. When these pedagogies are in place, I see students in a ‘learning flow-state’, where time passing goes unnoticed.

Ākonga are bursting with passion and excitement, spending hours actively problem solving, not realising time is passing, creating learning euphoria and wellbeing. Designing, building, testing, failing, trialling, feeling the full joy of learning just like they did in pre-school where the systems were truly student-centric and equitable. This form of learning design transcends time, place, events, internet and device access, as it is grounded in the ability to work together to find solutions. It gets to the depth of what it is to be human, connecting at our most basic level.

The disobedient, disruptive classroom appears chaotic and disorganised from an external view. Look more closely and you will see undetermined problems and solutions being discussed, co-constructed, solved and collaborated on, educators and learners side-by-side. Failures are embraced as valuable learning opportunities. Students who know how to design, jump between stages and steps, model, test, evaluate, present, and refine as their process demands they do so. As they develop this capability, they begin to, unknowingly, design themselves.

Quality learning design – an authentic experience

A Year 12 student is learning in a focused local curriculum environment; alongside community businesses providing support and materials designing and building a Hobbit playhouse for a new space at the nearby community pre-school. Normally this is a young man who struggles with self-confidence, fitting in, numeracy, literacy, dyslexia and dyscalculia, and grasping scientific principles. During this authentic learning experience, he is not at all aware of his ‘academic’ personal learning challenges, or that he is exemplifying assessment for learning strategies. He has stepped into his creative, observational, empathetic, caring, human, and innovative logical mind, driven by the authentic needs of the pre-school children he is designing for. His desire to earn NCEA credits is nowhere to be seen.

Credit: photo by Joshua Harris on Unsplash

In one part of this design project, he is communicating his creativity visually, modelling a Roman arched window using Autodesk Inventor (free student industry standard computer aided design (CAD) software). Using this complex visual design modelling software does not highlight his learning challenges, it bypasses them, and instead uses his refined cognitive abilities to make alternative and usually more efficient creative and innovative connections.

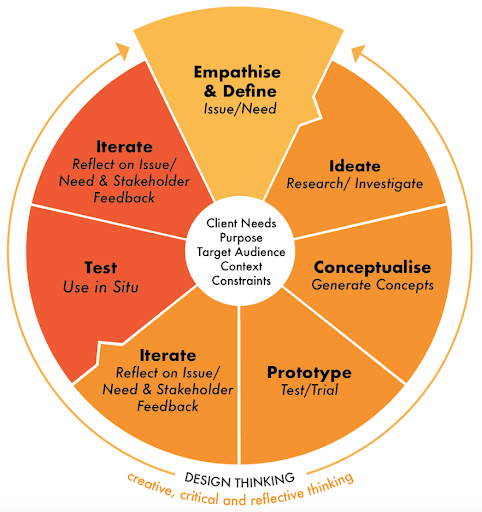

The iterative problem solving design process, requires him to seek out particular knowledge, understand, then do, act, as it is needed. Not focusing on his existing knowledge or lack of, the design process has guided him to understand and do. He has designed an outcome to improve the lives of a range of very young tamariki. Without realising the complexity he has achieved, he has applied the static physics, calculations and principles of forces of a Roman Arch – hoffnerphysics into his Hobbit playhouse, designed and custom built in a complete end-to-end process. He has drawn on the disciplinary knowledge of maths, science, technology learning and without noticing, has understood and applied understanding of principles he needed to, when he needed to, in order to successfully create a completed, quality outcome. He has demonstrated exceptional standards of oral, written and visual literacy, is authentically collaborating, gathering data, feedback, advice, sharing with and learning from his classmates who are also engaged in problem-solving, authentic and unknown, design thinking mode, and he is enjoying it!

Perhaps best of all in our current environment, he is empowered by designing for equity. He has made the circular entry door wide and high enough with a cobbled ramp access, the interior furniture and the window sized to be accessible for all ages and sizes of preschoolers, toddlers to 5 year olds including the 4 year old cerebral palsy girl in a wheelchair. With support from his local marae, the walls of the playhouse are decorated with poutama, tukutuku symbolising genealogy, learning and achievement. There are textured images from the fantasy trilogy, labels are 3D printed in braille, and movie filming locations are shown on a map of Aotearoa.

Learning design for wellbeing

Best of all, he exudes passion, deep happiness and satisfaction, as he immerses himself in his own measurable and accountable, lead-follow-lead design process. He doesn’t notice when he has completed requirements of multi-disciplinary achievement and unit standards, almost invisibly guided in the potential quality of those outcomes by his disruptive educator. He isn’t thinking from a place of 'self’ as he moves through his challenge, he isn’t counting credits, ticking NCEA boxes, he is feeling the same joyful learning experience that the pre-schoolers he is designing for are in.

The educator is in a supporting, observational role only. Design capability was established, strengthened and progressed during his Year 7 to 10 schooling. At senior secondary level, he is experiencing the freedom to be agentic, independent, resilient and autonomous, using these years to demonstrate his capabilities that step up naturally each year.

This learning strategy is not only great for his wellbeing. It reduces educator stress, workload and increases professional enjoyment. The educator can now be re-positioned to an agentic, 'aside' the learner role, noticing where and how during the process the student demonstrates specialist learning, the levels and disciplines the learning draws from, and is evidenced in. The educator collaborates and co-constructs learning design with other learning area specialists for guidance and advice as is required. Formative feedback is used throughout the process, as and when needed to ensure the learning evidence is documented and demonstrated clearly, for others to follow and give feedback on. This demonstration and documentation relies on digitally fluent students to draw on appropriate digital tools to use, record, design and transform their ideas into a feasible outcome.

The completed outcome and design process documentation folio, provides evidence of assessment for learning across science, maths, technology (materials, digital and DVC technological areas), Social sciences and English, with over 40 credits at NCEA Level 2 and 3.

An interesting human observation of this classroom is how effortlessly ākonga transition into a creative-flow state. They are busy, engaged, and time passes very quickly. Reactions to the bell signalling the end of the session, is often unheard, and mostly unwelcomed.

Perhaps this is because ākonga have the opportunity to be designers and have responsibility for the design process, so feel the accountability, the views, culture and needs of the real people, stakeholders and end-users they are collaborating with. They are designers of ‘things’, products, systems, environments, spaces, and ultimately, themselves as emerging adults.

Design creativity being the most basic of human activities requires the highest order of thinking. To ‘intervene by design’ (the essence of technology/STEM/STEAMS learning) is to improve our environment and the things in it that humans use.

Design creativity involves many forms of thinking and forces the designer to both draw on existing understanding, and to seek out new knowledge to fill identified and obvious gaps.

Critical and ethical thinking – understanding the needs of people and place what is, what could and should be.

Collaborative, community, and evaluative thinking – reacting to and taking on board feedback from the environment, stakeholders and end-users. Creating outcomes for others, develops equity thinking.

Creative and innovative thinking – developing resilience to test, trial and explore unknown concepts to see how well they may perform, be ‘fit for purpose’.

Thinking and learning in authentic, unknown contexts is both meaningful and engaging for all students. For students who learn differently, those with mild to severe learning needs that traditional learning often excludes, find themselves easily excelling as their creative connective brains thrive in this design environment. Design and its reliant thinking capabilities, develops students skills and understandings into real-world ‘event-proof’ capabilities.

If we are courageous enough to be proactive rather than reactive, we could use our current complexities and challenging events to shine a lens of designing for equity in our classrooms.

Learning design for equity

Could the most important focus be on how we design high quality classroom learning that develops capabilities in creativity, critical thinking, innovation, communication, collaboration, empathy, patience and resilience, challenge and question bias, where the vision, goal and outcome demonstrate equity? Being able to design effective and high quality learning has always been the core role of educators, but how many of your colleagues actually know how to design learning that is measurable, accountable and meaningful?

Maybe a shared definition of future focused high quality learning design could be one that is measurable in how it contributes to equity, supports learner transition and progression, provides that elusive future focus we are searching for?

Traditional systems and disruption

Across all ages and year levels I have seen the students of these ‘disruptors’ regardless of being 5-years-old or 18-years-old, demonstrate passionate, meaningful, connected and transformative learning.

“projects, passion, peers, and play. In short, we believe the best way to cultivate creativity is to support people working on projects based on their passions, in collaboration with peers and in a playful spirit. Most schools in most countries place a higher priority on teaching students to follow instructions and rules (becoming A students) than on helping students develop their own ideas, goals, and strategies…. Opposite: I believe the rest of school (indeed, the rest of life) should become more like kindergarten.” (Resnick, 2018)

So do we want academic, credit-counting students, or do we want healthy, resilient, creative, collaborative students who will become the adults of our future society?

Perhaps best of all these things, this design approach to high quality learning has the biggest positive impact on personal hauora, resilience, connectedness, and wellbeing. The disruptive ‘events’ that we have and continue to experience are significantly impacting the hauora of our rangitahi and tamariki, their whānau and communities.

We understand that our education systems are no longer ‘fit for purpose’. The increasing numbers and frequency of ‘events’, are handing out a pounding and an opportunity to school systems. Some systems, (such as streaming, timetabling and hierarchy of learning areas) are clearly not only not serving the needs of our present learners, educators and communities, they are often creating very real barriers that damage the learning and the child.

Disruptive and disobedient educators

These disruptive and disobedient educators also go beyond their own classroom and school systems, by making small changes that disrupt traditional barriers. They bypass transition systems, building relationships with local year six, seven and eight primary educators, maybe through kāhui ako networks, so they can get meaningful student data to enable their goal of a ninth year of learning. Within their own school systems, these educators are creating strategies to ensure they can teach the same class of students in year nine and ten, so that learning is consistent, coherent, and correctly prepares the student for success at NCEA. In our Hobbit playhouse example, the educator made sure all students had deep design capabilities, confidence in collaboration, community connectedness, and could authentically experience joyful learning and relive their preschool experience by being creative. They had permission over a sustained period of time, to enjoy and celebrate failing that developed sustainable levels of resilience, self awareness and critical consciousness.

In Disobedient Teaching: Surviving and Creating Change in Education (2017), Welby Ings describes how external events and disruptive/disobedient educators sit within current educational systems:

"As educational institutions perceive talent, few innovators are attracted to professional structures that expect them to be a cog in a machine. Highly innovative people may train as teachers, but they rarely stay long in the systems.” (p.127)

As we hear so often, those with the passion and desire to redesign the systems, the ones we need for things to change, likely leave despondent, burnt out and exhausted.

So if negatively impacting events like covid, earthquakes, floods, acts of terror, abuse and crime within our communities, are likely to continue, then maybe it is time to consider, what is the core role of educators? Is it to be disruptive and disobedient to the educational systems they exist within? And if so, what does this mean for our classroom educators, communities, leaders, and decision-makers?

What can each educator do then? Being responsible for a classful of sponge-like minds is the greatest privilege of any adult. Education is society's biggest R&D opportunity; to research the next generation, to design and develop the required future.

So what about sustainability and longevity?

Rejecting short term thinking and ineffective systems, learners who experience high quality future-focused learning, will then contribute to the ‘thinking-long’ philosophy by becoming transformational members of society, in groups with strengthened community hauora, equity, connectedness, resilience and patience.

Surely learning that remains in the heart and minds of learners, that could rise above and resist the impact of external events is the goal for all educators wherever we are in the system?

We have heard about this learning ‘utopia’ for many years from Sir Ken Robinson, Michae Fullan, Derek Wenmoth and others, about the ‘thinking-long’ approach where school systems, timetables, local and national political cycles could be designed to serve seven future generations, rather than then year/three year/term goals, ERO cycle, or reporting schedules.

Our wero?

Our wero is currently to design new and equitable ways to deliver learning. Could now also be the time to re-focus on ‘the fundamental task of teachers’; meet the needs of every student for the whole of their schooling by being adept designers of high quality, future focused learning and systems, that will safely ride the waves of any external ‘events’ and evolve the no-longer fit-for-purpose systems we exist in?

Talk to us at CORE if you want to explore the possibilities raised in this thought piece with one of our professional learning facilitators.

Author

Catherine Frost

Catherine supports schools and kāhui ako to create meaningful and measurable change through effective, future-focused strategies. Across almost 30 years of working in education, Catherine has used an equitable design theory approach – identifying needs and problems, then designing and implementing a strategy to bring about the required changes.

References:

Ings, W. (2017), Disobedient Teaching : Surviving & Creating Change in Education, Published by Otago University Press

Resnick, R. (2018) Lifelong Kindergarten: Cultivating Creativity through Projects, Passion, Peers, and Play, Published by The MIT Press

Wenmoth, D. (2022) retrieved from Futuremakers website

Explore more content

Explore our wide range of education related podcasts and blogs, ranging from experts discussing Kaupapa Māori, Cultural capability and te reo Māori, Leadership, Pacific viewpoints, Digital and innovation, Inclusive learning and more.