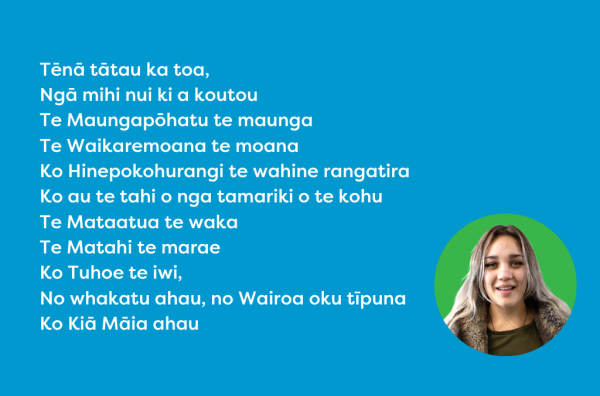

From the other side of the fence - Part 1

Māia's journey - Let's break it down

Wahine Māori, Māia Goldsmith, faced multiple challenges from an early age. She was suspended, stood down and expelled – three times. Today, Māia has recently gained her second Bachelor’s degree. Her story shares what it was like to be “excluded from the education system” and the impact of being labelled an “at-risk” rangatahi.

Touching many hearts, Māia talked about her journey at uLearn21. “I hope to give you a deeper insight into how you as educators can interact with these bright but damaged youth and how the education system is the place to build life-saving bridges.”

Taken from her activator session at this year’s conference, this two-part blog shares Māia’s story.

This blog contains sensitive content, which may be disturbing or traumatising to some audiences. Discretion is advised. If you or someone you know may need support please contact Sexual Abuse Education NZ https://sexualabuse.org.nz/.

Disruptive, aggressive, confident, loud, charismatic, friendly but intimidating and unable to follow the rules; troubled and trouble – words often used to describe kids like me in the education system. Usually followed by ‘we have many reasons for concern about your behaviour’ and ending with ‘you have so much potential we would hate to see you waste it’. Me and all my closest friends were expelled or ‘asked to leave’ high-school, some of us more than once. All of us Māori or Pasifika, all from what are considered ‘broken homes’. All with wide ranging traumas and experiences that none of our classmates or teachers could even begin to imagine.

Labelling and institutional rejection have strong impacts, creating mistrust and resentment within these kids that continue into adulthood. They contribute to the cycles of crime, poverty, unemployment, low-education, abuse and trauma, solidifying the ‘us vs them’ mindset and damaging an individual’s ability to succeed on both sides. As someone who has jumped the fence, I am here to open that space and talk about how we can do that for the kids still falling through the cracks.

- Why are they so disengaged? Distracted? Disruptive? Angry?

- How can they speak like that? Dress like that? Drink? Smoke? Swear?

- How do we get through to these kids? Should we bother?

I will follow four main themes:

- The making of an ‘at-risk’ youth: Here we will explore how I grew up, what was normalised to me and kids like me. How these experiences eventually clashed with my participation in mainstream education, leaving me labelled, excluded and seen as a damaged young girl, placed in the ‘too hard’ basket.

- My experiences as an ‘at-risk’ youth: Continuing on from the first theme into how those experiences played out in the school system and what that looked like

- What I learnt from these experiences: As I grew up and reflected on my journey, what I learnt about me and kids like me, and what might have made a difference.

- Thoughts for your practice: This will be the focus of the second part of this blog, where I will look at some recurring interconnected themes.

My journey is often considered shocking and unique by many in ‘this world’. But many children and young people in Aotearoa have very similar experiences to me. As you listen, I would like you to remember that these events are not rare. Almost all the kids I grew up with have lived experiences like mine.

The making of an 'at-risk' youth

I am just one of many, and just one of those to jump the fence and get qualified, so people like you will hear me. Mine is a story of violence, and fear, of abuse in all its forms, of running and hiding and never really being safe. It’s a story of intergenerational poverty, trauma, and mental illness, and the resulting social, behavioural and physiological issues that follow from these experiences. And it’s a story that many will understand.

The more time I have spent analysing this story, the more I understand how it plays into intergenerational poverty and abuse that has followed on from the impacts of colonisation on Māori wahine. This story begins with my grandmother, giving birth to my mother on the floor of a shack with no electricity in rural Wairoa, with two broken ribs and a fractured spine after receiving another severe hiding from her husband. It’s her fleeing that abuse to the South Island ten years later, struggling in desperate poverty to provide a chance for a better life for her five children.

It’s my mother, being awfully bullied at school for her ‘Māori accent’ and the holes in her shoes. How she suffered a sexual assault at 13. How, after a lifetime of abuse from her father (and still having absolutely no contact with any formal or informal support system) she found that familiar violence in her mid-20s, when she fell pregnant with my younger brother to a member of the Mongrel Mob. It’s the story of lived experiences from the women closest to me, horrific and painful stories…I would not understand the depth of their impact until I arrived at Uni, discovering how different family history was for so many other kids.

These experiences are part of my story too, largely shaping my life as a young girl. From around the age of two, ten years of my life was spent on the run, in and out of Women’s Refuge, police stations and court rooms. Life meant being witness to sexual assault, a whole culture of extreme and cruel violence. We spent time in Mataura and Ohau down South in the shearing sheds, where alcohol, drugs, sexual abuse and domestic violence were daily occurrences, like clockwork. Every child there was exposed to it. The Mongrel Mob is hugely present there – meth, violence, prostitution and gangs are normalised occurrences. From an early age, authorities and institutions were targeted as enemies, as intruders and interrupters of our lifestyle.

I started school in Seddon, under different names in witness protection. I think I was at school for about six months before we were found. I remember him jumping in the back seat, putting a knife to my mum’s throat and threatening to kill us all if we left. When he got out, my mum floored it and we were gone. We moved then, twice, and again six months later, to Motueka by the time I was six. He was eventually jailed for a long period of time. We had a chance to breathe and finally managed to make a life for ourselves.

As a child, I did not know the things I had grown up with weren’t normal, that cooking, cleaning and taking care of your siblings day-in, day-out wasn’t something most ten year olds did. Having seven step siblings, three different families, three different houses at Christmas wasn’t abnormal, and they certainly weren’t ‘bad’. My experiences were just my life, and they still are, until people reacted to them.

My experiences as an 'at-risk' youth

I was sexually assaulted at the age of 11. Like most things I had lived through, I didn’t speak about it to anyone. It was something I had witnessed many times before, something I had come to understand as a part of life. And I buried it, along with everything else that was painful and scary, and just carried on as normal. Nearly a year went by, and I hadn’t said a single word to anyone, but eventually confided in a friend. Unfortunately this did not go well, resulting in an outburst in class. Teachers quickly got involved and I remember feeling like everything was about to completely explode. Within the hour I was sitting outside the staff room, alone, while my teacher and senior staff discussed what they should do. I wasn’t allowed in, I wasn’t allowed back to class, I had to stay late. I felt like I had made a huge mistake and done something very bad. This was the first time I experienced the ‘drowning’ sensation I got used to as a teen and young adult, gasping for air on land.

They sat me at a desk and questioned me, saying I needed to tell them so they could help me. I wouldn’t tell them. I just wanted to go and eventually they let me. I walked home alone, finding a police car and two police officers telling my mother what they believed had happened to me, without me even being there or being made aware. A total sideswipe.

I didn’t know they would be there, let alone informing my mother I had been raped, without my presence or knowledge. It was totally out of my control, I was just watching it all unfold. I could see the devastation in her face, the guilt and the blame and I felt totally responsible. My role in the family was to take care of my brothers and help my mum, and this, this wasn’t that. I felt betrayed by the system, like they had intruded on my life, torn it open, inserting themselves and their procedures on me and my family, with no thought to how I felt or what I wanted.

It was like being raped again – by a system that was given permission to do so. I was so angry. In my mind, it wasn’t anyone else’s experience, it hadn’t happened to them. And yet I had to explain it, justify it, relive it, so that they could fulfil their ‘processes’. No one explained to me what was happening, what would happen or why. The handling of sexual assaults and abuse by authorities is a topic we could find endless criticisms on and an area in much need of support. For time’s sake I will not get into it right now, but this was devastating and everything changed after that.

This was significant for many reasons. It made reality of a memory I had pretended was just a nightmare, it devastated my mother and, when it came to institutions and authority, it really solidified my feelings that it was me vs them. At the time, the upheaval of my life was once again attributed to the intrusive ‘caring’ adults (who didn’t know s*** about me or my life). I was angry, blaming the school for the humiliation and isolation I now felt. I knew men could be bad, what I didn’t understand was trust being broken by the system. School had once been a safe place for me – now it was a trap.

Less than six months later, four weeks into year 9, I was expelled from high school for the most drugs ever found on a student in the South Island. Weed, pipes, tobacco, vodka, lighters, papers, everything. Me and a few other kids were caught up in the ‘incident’ and I was considered the ‘ring-leader’ as I had supplied most of the substances. The turnaround was unbelievable, from leadership awards and sports trophies to exclusion and front page news. I’d had maybe one detention throughout primary and intermediate, now all of a sudden I was outside the staff room while teachers discussed what to do next.

Perhaps I was a ticking time bomb, perhaps what came next was unavoidable. But I can look back now and clearly identify the series of self-destructive choices that quickly had me looking at myself as a sexually active, drinking, smoking thirteen-year-old girl, wearing heavy makeup and inappropriate clothing. I now understand this was a sort of armour, a protective shield, someone else I could be that was tough, unashamed, secure, brave – a way of taking control of me, for once.

I was seen as a highly ‘at-risk’ youth that was also ‘a risk’ to others. This was the first time I heard these phrases (but certainly not the last). They somehow helped solidify my position on the outside of all these other kids. I arrived at the next school with that chip on my shoulder – and a preference for being ‘risky’ over being ‘broken’.

I remember them putting me in a class and buddying me up with some of the nice girls from the school. These girls were nice, they came from wealthy, two-parent families, had never drunk or smoked and barely swore. One of them straight-up told me she did not think rape was something that happened in New Zealand, or at all. They were from whole different worlds. They were nice girls, and as much as they wanted to, they didn’t understand anything about the life I had lived. It took me a long time to understand that was not their fault, and also a good thing.

These kids pitied me and my ‘horrible’ childhood. They were the same girls who, because they were worried about me, narked on me to teachers for smoking weed – eventually getting me expelled, again. The same girls whose parents successfully prevented me from re-entering the school a year later because I was a bad influence and a ‘danger to their kids’…‘privileged interference’ made by those who just have no idea. My efforts to fit in with them did not last long. Within months I made friends with other ‘at-risk’ youth, finding friendship and comfort in our shared experiences, bonding as outcasts in the school system.

I remember feeling like none of the teachers, counsellors or authority figures actually cared or understood us. They just wanted me to fit in the box and behave, thinking that would make it easier for everyone. Well I didn’t want to fit in the box and I didn’t want to behave. A huge lack of respect and trust for the institutions had festered and I didn’t really care what they wanted me to do. By second term year 10 I was expelled again. Within that time I had been stood down two or three times and suspended, as well as all the detentions, exclusions from sports teams and extra curriculars, subject withdrawals and many days in the toybox. For things as big as alcohol and drugs, and small things like wearing too much make-up, or putting safety pins in my skirt.

It doesn’t really matter once you’re the one of the ‘bad’ kids, each and every shot fired reminds you of that. One of my best mates was withdrawn for having fluro paint on her shoes, she literally walked in one side of the classroom and out the other. We met outside the Dean’s office, both waiting for punishment or approval. To me, these were very clear messages that I was not accepted here, that we weren’t accepted here, that we weren’t good enough for this place and didn’t belong here. Eventually I convinced myself of that. As an adult, I recognise anger and outcasting was easier than pain and sadness, and the addictive comfort found in chaos and turmoil was difficult to overcome.

What I learnt from these experiences

I was on a mission to prove I wasn’t good enough, that I was bad, and broken and not worth anyone’s time, just like all the teachers and police thought I was. I was expelled again, sent to local alternative education that same day. This place saved my life. (For anyone who really wants to make a difference for ‘at risk’ youths – work here and get them more funding!) The people there do the jobs of teachers, social workers, counselors, parents and police (on funding peanuts), and the system calls it tutoring.

This place did many things, but a few will be most relevant to you as educators. It allowed for compromise and growth in a way that was different to mainstream schooling. Rules and structures were not immovable and rigid but related to our behaviour and participation. We had active roles in our learning and were given responsibility for different aspects of our environment. We weren’t immediately excluded from class for the way we dressed, spoke, our makeup, or small behavioural outbursts. It was a place that allowed us to be loud, different and who we needed to be – and didn’t punish us for it. Many people ask me what helped me turn my life around. This place played a huge part in my sense of self-worth and ability to find value in myself as a young person.

I became close with one of the tutors there, he was the same iwi as me and had shared a similar childhood. He was real with us kids, gaining a lot of respect because of that. We would talk about the world and I would share stories of my life with him. One day he said “girl, you’ve been dealt a really shitty deck of cards, you really have, but you get to decide how you play them, that’s what your life’s about”. No pity or b***s***, just honesty that planted the seed in my head that I would be responsible for what happened next.

I started to look at my peers, realising we were all just damaged young people, punishing ourselves for things that weren’t really our fault. Ninety-nine per cent of us were Māori or Pasifika, all with different degrees of trauma and issues with families that didn’t care (or didn’t know how to). Young people in pain, causing pain. It suddenly became so obvious to me – I decided I wasn’t going to live life punishing myself for what other people had done to me. I decided I deserved better.

Nearly 12 months later they tried to get me back into mainstream school. We had a progress meeting and it was agreed they would allow me back in on a trial – if I behaved I would be allowed to return to finish my schooling. I was so excited, ready to return and prove that I could fit in and be good, just like everyone else. Unfortunately, my previous objective of being a scary bad kid had been achieved and the damage had already been done. The parents of the girls I mentioned earlier had called, laying complaints, saying I was a toxic influence, a threat to their wellbeing and safety. They would remove their kids from the school if I was to return. The school agreed, calling my mum, telling her I wasn’t welcome back. I hadn’t even stepped off the school bus. This third and final rejection from the school system was devastating and a huge wake up call. They weren’t going to let me back in, I had succeeded in solidifying my position as a bad and dangerous young kid. High risk and a risk to others, I had built a hideous reputation for myself. If I wanted a second chance, it wasn’t coming from there.

I got angry, again, but differently this time. I was angry they had dismissed me and my efforts to change. They failed to acknowledge I had learnt from my mistakes and was begging for a chance to prove myself. I decided I’d use that anger to prove myself to them anyway. I used to joke that one day the school would employ me to come and give inspirational speeches about my success – this is my second presentation like this, this year!

At 15, after the third rejection, I left home and my hometown, moving to Christchurch with my boyfriend. I didn’t really have a choice, no institution in the Nelson region would take me.

I met another influential tutor my first year in Christchurch, a fearless Māori woman who’d had her first baby at 16, left home the same year and knew the struggle. She was tough as nails and bent the rules. She eventually got fired for helping me sort my Youth Allowance, giving me clothes and food so I could survive, and an array of similar ‘boundary-crossing’, yet life-saving, actions. Actions that made her hugely valued by students and a lifelong friend. She demonstrated to me that you can jump the fence, make something of yourself and truly make a difference in people’s lives.

She was a fierce role model, an example of what I could be for young people who grew up like we had, if I chose to. She was also a reminder that ‘ticking boxes’ and ‘minding tape’ would always be present. That the differences in how we care for each other, how we bridge the gaps, is vast. And I would have to learn to play the game and become highly qualified to make real change at the highest levels. It was a challenge to my younger self, to prove everyone wrong, take that life I deserved and show all the kids like me that they deserved it too.

She also showed me that people like us needed a place in that world, even though we were punished for our different conduct, that it mattered. That in the spaces and institutions where these worlds meet, there are huge clashes of culture. I’ve recognised these as being deeper than just ethnicity, but clashes of class culture and of what was or is considered acceptable conduct in mainstream society.

In the years that followed, I would win student of the year, complete a diploma in Beauty Therapy, enrol myself in anger management and, eventually, many different forms of therapy. The Diploma gave me the NCEA level needed to enrol at Uni, so in 2017 I did.

No one in my family had ever been to Uni and not finishing school past year 10 meant I did not qualify. Applications and enrollment were a struggle in themselves. It’s safe to say I struggled mentally with PTSD, anxiety and depression, due to the nature of my studies, as well as physically and financially, like many students do. Nevertheless, I graduated last year with a Bachelor of Criminal Justice and this year I will complete my second Bachelor of Arts in Māori and Indigenous Studies, Political Science and Human Service.

I think a huge part of my journey to University (and from there to today), was finally being in control and responsible for myself. The good, the bad, the failures and successes were mine to take, not hindered by expectations or barriers of what I was supposed to be. And I’d made the decision that I was to be great. I was going to make something of myself and create a life I deserved.

Explore the second half of Māia’s uLearn21 session in Part 2 of this blog.

If you or someone you know may need support please contact Sexual Abuse Education NZ – https://sexualabuse.org.nz/

Author

Māia Goldsmith

Ngāi Tuhoe me Ngā Whakatohea Wahine Māori, Māia Goldsmith, faced multiple challenges from an early age. She was suspended, stood down and expelled – three times. Today, Māia has recently gained her second Bachelor’s degree. Her story shares what it was like to be “excluded from the education system” and the impact of being labelled an “at-risk” rangatahi.

Explore more content

Explore our wide range of education related podcasts and blogs, ranging from experts discussing Kaupapa Māori, Cultural capability and te reo Māori, Leadership, Pacific viewpoints, Digital and innovation, Inclusive learning and more.