Talanoa is for everyone: a guide for educators

Almost every day each of us has the opportunity to learn from, exchange ideas with, people who have different perspectives or cultural backgrounds. Therefore, it is important to understand the depth of the Talanoa approach that allows us to have respectful discussions and show dignity for others while enhancing our own effectiveness in a multicultural context.

What is Talanoa?

Talanoa is a traditional word used across the Pacific to reflect a process of inclusive, participatory, and transparent dialogue. Talanoa provides opportunities to discuss authentic knowledge grounded in Pacific values and principles of ‘Ofa | love, Faka’apa’apa | respect, Mālie | humour and Māfana| warmth. It is a format for inclusive, collaborative meetings and which encourages greater participation and where important contributions can be made.

Talanoa has been used by many people in everyday conversations, professional dialogue, research, and is used across many contexts. These conversations build and strengthen relationships between people on many levels. Using the talanoa process enables us to learn more about each other's backgrounds and gives us a better understanding of why we think, feel or act in certain ways. It is a way to unlock the ‘culture of silence’ for those who may have a fear of speaking up or of being culturally misunderstood.

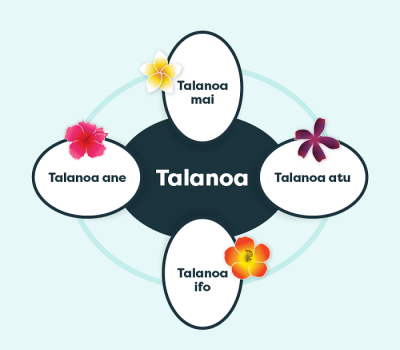

Talanoa has four aspects:

- Talanoa mai

- Talanoa atu

- Talanoa ane

- Talanoa ifo

While we have described these aspects separately, they are interwoven in every part of how we engage in talanoa.

- Talanoa mai is about inviting someone to share their thoughts or stories about any topic. This is a space where people will be able to share their thoughts openly, where respect for others is significant.

- Talanoa atu is to respond to the person/people involved and engaged in the talanoaga | conversations.

- Talanoa ane is to talk with someone who is in close or distant proximity to you.

- Talanoa ifo is a reflection about your inner self and how you are going to respond.

Examples in action:

We will apply these aspects to three contexts:

- Coaching and Mentoring

- Research

- Recruitment.

Coaching and mentoring context

In some circumstances a coach/mentor can come to a meeting with some preset ideas and plans to help the mentee. This is sometimes what is needed. However there are times when it’s valuable to begin a meeting with open minds and to empower the mentee to explore, consider and develop a range of options for themselves, rather than just giving them the answers or solving an issue for them. In this coaching and mentoring context, the coach/mentor uses Talanoa mai where the mentee feels comfortable and safe to share their thoughts about their expectations, aspirations and challenges. Additionally, the mentor is open to providing a safe space that will allow the mentee to be open to express and explore ways for them to grow and thrive.

Talanoa atu is where a two-way process happens as the mentee responds to the coach/mentor while the coach/mentor listens then responds back. Throughout these interactions the key values of mafana | warmth, mālie | humour, faka’apa’apa | respect and alofa |love are embedded and reflected.

Sometimes when we are unsure about something we invite others’ perspectives. This is a key aspect of Talanoa ane where reciprocal learning through collaboration takes place. Through coaching and mentoring talanoa ane often happens and ensures we are all on the same page.

During the coaching and mentoring process participants will be engaged in many reflective processes. Talanoa ifo demonstrates how self-reflection and inner thoughts are a critical part of mentoring and coaching and offers the mentee a quiet space in which to reflect on issues on self and on interactions with others. For mentors this is shown by an ability to critically reflect on their own practice to improve and further develop their skills and implement different mentoring strategies and approaches.

Research context

Recently we have worked on a research project funded by the Rātā Foundation. We investigated how to support Pacific learners and their āiga (families) as they transition from early years/preschool to school. The Talanoa model approach was used in our research to gather stories and experiences from Pacific āiga and fanau about what successful transitions to school look, feel and sound like for them.

Examples from this research project describe how the four aspects of the Talanoa process were used to engage āiga, tamaiti (children), teachers and leaders.

Talanoa mai:

We recognised the importance of hearing, understanding and valuing the place of Pacific identities, languages and cultures as a key element for successful transitions. Through the talanoa mai process the teacher-researchers were able to empower āiga and tamaiti to engage in talanoa to share their aspirations and what matters to them. The use of resources enabled tamaiti to share information about themselves and their āiga in natural and authentic ways.

Talanoa atu:

The teacher-researchers were able to discuss and share their understanding and interpretations of Pacific values and the cultural metaphors that were embedded in this research project. Talking straight from the heart opens up space for greater empathic understanding.

Talanoa ane:

During the research many conversations happened where thoughts were shared with others, within both small and large groups and to ensure we are mindful of the silent and quiet voices and allow time and space for these to be heard.

Talanoa ifo:

The research journey created spaces for teacher-researchers to reflect on their own practices. One of the teacher-researcher’s reflected about the environment and began to ask herself this question; Is this classroom mine or ours? This enabled her to read more articles related to the topic and sought others’ feedback that led to her change in approach in recognising the value of ‘ours’ as opposed to ‘mine’. The outcome of her self reflection is that the classroom is everyone's responsibility. This change in practice summed up with Bernstein’s quote that:

“The culture of the child cannot enter the classroom unless it has first entered the consciousness of the teacher”.

Recruitment context

Traditionally the recruitment process happens by inviting the applicants to share their stories and experiences, and in the ways they respond to questions to make a good impression on the interviewers. When we think of this Western approach we recognise that this does not fit well with Pacific peoples and the ways we engage in conversations and decision making.

Using the talanoa mai approach enables us to share thoughts, ideas, experiences and stories through open and natural conversations rather than through the expectations that questions are asked in a particularly structured order.

In a recent experience a Pacific interviewee expressed that when he heard that he was going to have a Talanoa he felt greatly relieved. He had been nervous about needing to respond to formal questions. During the process of talanoa his thoughts and stories came to light naturally through mafana | warmth, mālie | humour, Faka’apa’apa | respect and alofa | love.

Talanoa atu:

During the above interview process the panel of interviewers were listening and joining in with the participant. The value of having the panelists actively listening with the whole body, spirit and mind helped the interviewee to feel safe and relaxed as they engaged in shared conversations and stories.

Talanoa ane:

The panelists were able to invite others to add or contribute ideas during the interviewing process as they clarified any gaps in information they were seeking. Additionally there were opportunities for the interviewee to share further information.

Talanoa ifo:

When the interview process was completed the panelists reflected and reviewed how the interviewing process went. This helped them to implement any changes for ongoing improvement. The interviewee was invited to share their feedback about the process as well. In the previous interview example the interviewee expressed the following feedback about his experience in the Talanoa approach to his interview:

“My impressions of the online Talanoa were first and foremost, the interview panel greeted and acknowledged my presence in Samoan through the process of fātulima (informal welcome) followed by a tatalo (prayer) asking God to be present in the Talanoa. This process of the fātulima and opening tatalo made me feel very comfortable and that the welcome mat (fofola le fala) had been rolled out for me so we could engage and Talanoa at the same level even though this was a job interview for the position. Following the tatalo, then the formal process of fa’afeiloaiga (welcome) where a representative from the organization welcomed me in the Gagana Samoa and then I was given the chance to reply. Once the fa’afeiloaiga process was completed the rest of the panel introduced themselves and their roles. I really felt a sense of belonging that my voice and opinion were valued not challenged. I left the Zoom interview feeling that my mana which can be best translated as a combination of presence, charisma, prestige, honour, and spiritual power had been uplifted through this approach to the Talanoa Concept.”

Conclusion

While the demands of today’s intercultural settings make it impossible to master all the do’s and don'ts of various cultures, we believe there are certain behaviours that should be modified when we interact with different cultures. For example, verbal and non verbal interactions and messages can convey different meanings across cultures by understanding situations that people bring with them.

In what ways can you ensure that when you engage with others that the four aspects of talanoa (Talanoa mai, Talanoa atu, Talanoa ane and Talanoa ifo) are reflected and honoured?

How do you know that the four principles of talanoa (Ofa | love, Faka’apa’apa | respect, Mālie | humour and Māfana | warmth) are grounded in your conversations and interactions with others?

References:

Bernstein, B. (1970). Education cannot compensate for society – a bit. New Society, 15(387), 344-347.

Vaioleti, T.M. (2006). Talanoa research methodology: a developing position on pacific research. Waikato Journal of Education, 12, 21-34.