Voices from the Pacific - Lost in translation

E lē falala fua le niu, ‘ae falala ona o le matagi

The coconut tree doesn’t sway on its own, but is swayed by the wind.

How do we define culture? Who is responsible for developing one’s culture? What measure and importance is given to an individual’s culture? At what age do we develop a good understanding of who we are and where we are from? What role as educators do we have in acknowledging the culture of our learners? This blog aims to challenge our thinking, question our personal judgements and encourages us to distinguish perception from reality. Information and statistics included in this blog have been developed from the perspectives and results of collated research data from 30 ākonga, both male and female, from 8 – 18 years of age across Te Tai Tokerau and Tāmaki Makaurau who identify as Tongan, Samoan, Niuean, Cook Islands and Māori.

For some of the questions posed in the opening there is not a clear answer. However, they do draw attention to the inequities, confusion, and at times frustration, felt by ākonga as they to begin to ask themselves who they really are. Do these infants, toddlers, children and young adults transition from their homes to their educational contexts with the same values, beliefs and teachings that they share with aiga (family)? Are we encouraging them to bring their kete (basket) of knowledge or are they leaving it at the door on their way in? Do we inadvertently ask them to step into another world that may be foreign to them? The Ministry of Education draws attention to this, ‘Pacific peoples are one of the larger ethnic groups in New Zealand, with the highest proportion of children aged 0-14 years. It is estimated that the number of Pacific learners will increase from 10 to 20 percent of the total school population by 2050’ (2017, p.1). As educators we have an important part to play, starting with pronouncing their names correctly.\

What cultural lens do you see through?

Cultural identity through a Pasifika lens may look different from how we imagine as educators. We cannot learn about a culture from attending pre-service teacher training or from reading textbooks. We need to understand the struggle that many of our young Pasifika people face today. Growing our understanding is a critical part of changing mindsets. Our classrooms provide forums where they can feel validated, and where their messages are heard. The research data highlighted how deeply ambivalent ākonga feelings are towards education. Despite what we perceive to be a culturally responsive curriculum and delivery in New Zealand 66.7 percent of learners have had their name mispronounced or have been referred to, and compared against, another family member who has been a past ākonga at their current centre or school. Therefore, their identity as an individual feels lost as they are always stepping into the footsteps of another member of their family. As one ākonga stated in a 1:1 interview, ‘we are expected to respect the names of all the adults in our school…I feel that we deserve the same respect’, ‘you only need to ask me how to say it and I will help’. Another stated, ‘saying my name right is important to me’. Due to similar experiences across cultures, one ākonga in Auckland has created an app to support educators in their pronunciation of student names – Pronounce App for Educators.

Showcase my talents

This voice recording is taken from the voice of a 14-year-old Tongan-born male when asked to write his first speech. He took this as an opportunity to change mindsets and when thinking about one’s own culture, some pertinent messages became evident. What makes our ākonga proud? What stereotypes do they want addressed? Here are some voices taken directly from ākonga who took part in this research:

- “We are just not your normal rugby players, fast food workers, bus drivers,

road workers and that we are more than what statistics say we are” - “That I show who I am for myself and for who I want to be”

- “Knowing who I am as an individual and how my heritage, upbringing and understanding of society impacts that”

- “Acknowledgement of my cultures is a proud moment in itself”

- “My culture values and beliefs are important to me”

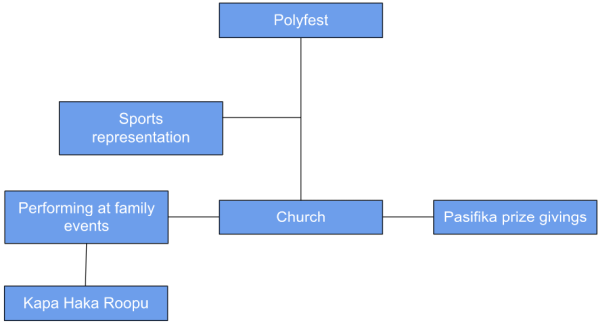

When asked to name a time in their lives where they felt proud to identify as a Pasifika ākonga the most compelling statement from one Pasifika student about being a successful learner was, ‘when I achieved excellence in my NCEA results, as I often hear Pasifika

students achieved low results’. The data revealed other areas that were strongly centred around six main events they consider pertinent to who they are:

Celebrating, sharing and uniting people together through cultural experiences such as performing at Polyfest events leave a lasting memory for ākonga and families. Alistar Kata, a reporter and presenter for Tangata Pasifika captures North Shore schools’ journey to their Polyfest debut. She follows the journey, alongside Rosmini and Carmel colleges, as they create history by entering for the first time on the Samoan stage at Auckland’s Polyfest.

Speak to be heard not forgotten

Fakatumau ke vagahau e Vagahau Niue

Keep persevering to speak the Niue language

For many, language is the gateway to learning. Fostering, encouraging and sharing in languages globally is what makes us so diverse in New Zealand. Over 75 percent of participants in this project identified the importance and feeling of connections when speaking in their mother tongue. A common thread was the desire to learn a Pasifika language at school. With greater opportunities for children to attend bilingual early childhood centres, language opportunities diminish as they move on to primary and higher education. Opportunities to engage in a language other than English become limited with fewer resources, fewer educators who speak a Pasifika language and reduced emphasis on languages in each sector. How can languages be revived and kept alive in our education sectors? With 22 out of 30 ākonga not comfortable to speak their language in an educational setting, can we attribute any disconnect of engagement with aiga (family) and fanau (children)?

Over half of the participants felt that from early childhood onwards they perceive little acknowledgement that their culture has been cherished throughout their education. Siope (2013) argues that there is much more to being and becoming culturally responsive. It is not just about stories and legends. It is about talanoa, getting to know each family and their children, and understanding their life experiences. When questioned about who in their life believes in them 2 out of 30 responses identified a single educator that has had an impact on them in one year of their life. Aiga were the only other people stated in answers. These were not restricted to a nuclear family, rather names included extended family members both young and old.

Through sharing, celebrating and making those connections educators can make a difference. Educators do care. It’s asking those questions of ourselves. What do I do in my centre, school, learning space to ensure that those faces in front of me know they matter to me? Are there signs, messages, gestures that I share to show this? If not, what can I change in my current practice? The Ministry of Education cultural competencies framework for teacher of Pacific learners, Tapasā (2018) describes three Ngā Turu (support). Using this framework alongside The Pasifika Education Plan 2013 – 2017 (PEP), The New Zealand Curriculum (2008) including Te Whāriki (2017), there are many opportunities to capture, transform, engage, respond and celebrate in Pasifika success.

‘In a similar way that our ancestors journeyed across the oceans in search of knowledge, prosperity and growth, Tapasā seeks to guide and support teachers and Pacific learners, their parents, families towards their ‘destination’ – a shared vision and aspiration of

educational achievement and success for Pacific learners’ (Ministry of Education, 2018, p. 5). Resources and supports are available such as The Pasifika Success Compass, we just need to use them and act.

What makes me, me?

Interviews surrounding achievements with cultural groups, for example Pasifika cultural days, Polyfest and Kapa Haka drew attention to the connectedness that encompasses wellbeing and identity. Interwoven beneath each strand is a story that seeks to tell us who

they are, where they are from and what'1s important to them. When reflecting on what pivotal moments in their life where ākonga were proud to be able to explore their culture, the main themes that emerged were:

- The feeling of a sense of belonging

- Being able to perform in front of people and being able to gain confidence

- Celebrating our Pasifika heritage

- Singing and dancing being proud of where we come from

- Gaining respect from my friends, family and developing friendships

Te Whāriki Online draws attention to ‘Pacific voices’ through their spotlight with a focus on local curriculum, Pacific pedagogy and languages. The storytelling that emerges through a variety of interactions, images and experiences in the early years creates a sense of belonging that we are gradually losing as our children transition through their education. How can you prepare for the future? Is there a way to keep Pasifika storytelling alive?

Measuring engagement – How?

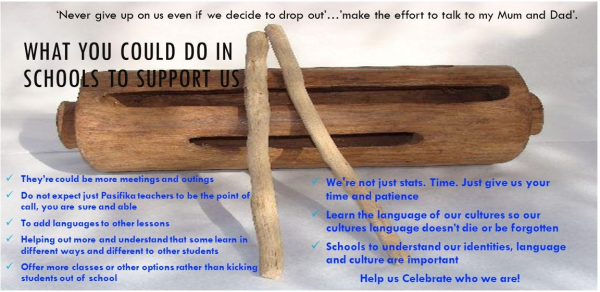

Is it necessary for ākonga to be facing the front of a class, watching an educator, focused during mat time or asking questions to be an active learner? Forty-eight percent of ākonga recorded that they think their educators view them as shy, quiet and reluctant learners. As one child shared, ‘Even though I am very shy, I still want to learn so if I don’t put my hand up it isn’t because I do not want to learn’. This message is clear. We must not give up. Misconceptions are sometimes ideologies we inherit as we move through our own life journey and experiences. However, it is how we respond to these that holds the most importance. Of equal importance, when speaking with ākonga of all ages, they want people to know, ‘we do care about our education’. This research revealed 73.3 percent believe that education plays a large part in their success as a lifelong learner. Pennie Otto provides a perspective through CORE EDtalks of cultural interactions of Niuean boys in secondary school.

Diversity at its finest

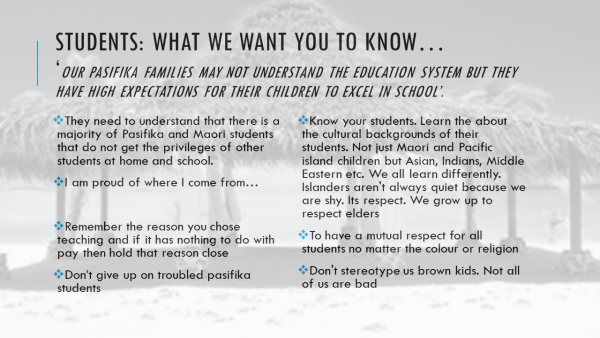

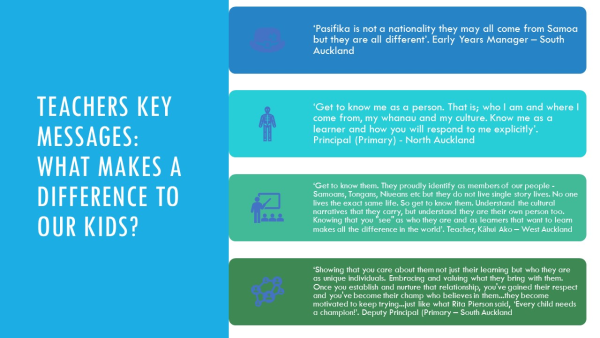

One of the CORE’s 2019 Ten Trends highlights the changing role of teachers ‘Deliberate provision of opportunities for ākonga to strengthen their own connection to their language, culture and identity which will in turn support teachers to respond to their learning needs’. Auckland, for instance, is often referred to as the melting pot of cultures. As one HOD secondary teacher shared, ‘know your ākonga. Learn the about the cultural backgrounds of ākonga. Not just Māori and Pacific Island children but Asians, Indians, Middle Eastern. We all learn differently. Islanders aren’t always quiet because we are shy. It’s respect. We grow

up to respect elders’.

Cultural responsiveness is a term that for some is another new language added to the repertoire of our education system. How this looks, feels and is viewed can be different for each person. As Pasifika ākonga in today’s world they are faced with many new demands, confusion and uncertainties for the future. Our centres, classrooms and learning environments need to be stable and safe places where our children can be themselves without feeling any judgments. This is not to suggest that they are uncomfortable, it is rather to reflect, observe, and think about whether the ākonga in our care feel a sense of belonging alongside their peers and educators. How nurturing are our environments?

In summary, when challenged on how ākonga feel about each other in various regions across Auckland, 56.7 percent believe that they are all different despite sharing the same or similar backgrounds and culture. No one area or people are the same. No two people look the same. Therefore, ‘know me, my values and where I am from’ (Pasifika Student, 2019).

References

CORE Education. (2019). Ten Trends. Retrieved March 19, 2019, from

http://core-ed.org/research-and-innovation/ten-trends

Ministry of Education (2013). Pasifika Education plan 2013-2017. Retrieved from

https://www.education.govt.nz/our-work/overall-strategies-and-policies/pasifika-education-pla

n-2013-2017/

New Zealand Government (2019). Ministry for Pacific peoples. Te Manatū mō ngā iwi ō te

Moana-nuī-ā Kiwa. Retrieved from

http://www.mpp.govt.nz/pacific-people-in-nz

Ministry of Education (2018). Tapasā. Cultural competencies framework for teachers of

Pacific learners. Wellington.

Pasifika Futures, (2017) Pasifika people in New Zealand- How are we doing? Retrieved from

http://pasifikafutures.co.nz/wp-content/uploads/2015/06/PF_HowAreWeDoing-RD2-WEB2.p

df

Siope, A. (2013). A culturally responsive pedagogy of relations. The Professional Practice of

Teaching, 18(2), 154–171.

Explore more content

Listen to our experts discussing the Pacific point of view on topics such as Matariki, Connecting through Talanoa, Aotearoa New Zealand histories, and Aotearoa's educational landscape.