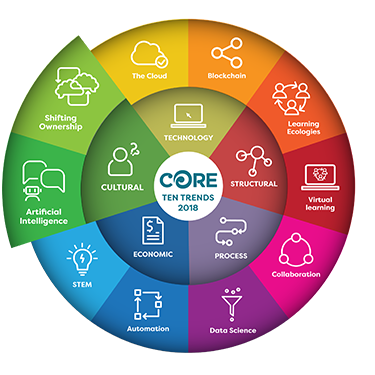

Shifting Ownership

What's it about?

The shift in ownership of learning signals a reversing of the "logic" of education systems so that the system is built around the learner, rather than the learner being required to fit with the system.

This trend involves understanding the shift from school and teacher-centric approaches to where learners are given greater responsibility and more opportunities to be active participants in all aspects of the learning process. Shifting the ownership of learning aligns with the idea that education systems must move away from an Industrial Age "one-size-fits-all" model that has prevailed over the past two hundred years.

This trend is evident in a number of initiatives and areas of emphasis that have been given priority both nationally and internationally over the past few years, including:

- Student centred approaches to education

- Self-directed learning approaches

- Self-managing learners

- Self-regulated learners

- Learner agency

- Student voice

Each of these have a lot in common, and together they provide a macro view of the elements contributing to this trend. While many schools and teachers would argue that these things are already happening (and they are), the real momentum is yet to be experienced at a system level, and will require changes to a number of the policy and resourcing frameworks that currently place the school and ‘structures’ of schooling at the centre of decision making.

Giving learners voice encourages them to participate in and eventually to own and drive their learning. This means a complete shift from the traditional approach of teaching compliance that develops a “learned helplessness” to encouraging voice where there is authenticity in the learning.

The concept of student agency transforms the notion of student voice to a completely different level. Agency invokes action, responsibility, mutual engagement and respect. The student is a “learning agent” whose self-efficacy makes the difference to their learning.

These two (voice and agency) are pre-requisites for the various expressions of student centred learning that are now being given emphasis, including self-directed, self-managed and self-regulated approaches. They are also foundational to other pedagogical shifts being promoted in many schools, including play-based learning, student-led inquiry, project-based learning and passion projects.

The common characteristic of all of these is the shift in ownership of learning – the increased enablement and empowerment of students to be active participants in the whole learning process, not simply in the learning activity, but in choosing what to learn, how to learn it and how it is assessed etc.

What's driving this?

The single most significant driver of this change is the appreciation of what it is our young people will need to be able to do, know and be in order to lead full and productive lives into the future, and to be contributing members of society. While it may be argued that this has always been the aspiration of education and educators, it is the image of what that future will or may be is what creates the need for us to re-think how we design and cater for teaching and learning in 21st century schools.

In an age of persistent and accelerating change, the ability to recall information is replaced by the ability to process it. An emphasis on problem solving, collaboration and citizenship is replacing traditions of conformity, compliance and ‘teach to the test’ that have characterised much of what has happened in schools historically. The OECD Nature of Learning practitioner guide supports the view of how important this is in preparing learners for a complex future, and explains how a clear sense of purpose will lead to more motivation for students.

In the New Zealand context, the 2012 Education Review Office (ERO) Education at a Glance report on priority learners states:

“In the most successful schools, the trustees, leaders and teachers have an uncompromising focus on fostering students’ interests and strengths, and on addressing their learning needs. They understand that their role is to serve students. Their philosophies about how students should experience education are lived out in rich learning programmes, thoughtful management of the curriculum, positive school cultures, and in effective leadership and governance practices. A synergy and coherence exists between these aspects that contribute positively to the whole experience of being a learner. Importantly, there is an ethic of care for students’ current and future success.”

The importance of serving learners, providing rich learning programmes, positive school cultures, and an ethic of care are all fundamental elements of the shift in ownership that is occurring at all levels of our system.

What examples of this can I see?

As mentioned above, there are already a great many examples of this shift occurring in our school system at present – for further insights see Learning to Learn, a collection of case studies and videos on the NZ Curriculum Website which provides a wide range of examples of where a shift in ownership of learning is already a part of how classroom and school programmes are running.

Shifting the ownership of learning is a little like teaching a teenager to drive – you can’t simply sit them in a car and expect them to ‘go’. It involves equipping learners with the tools, frameworks and strategies to help them understand, and therefore take control of, their own progress as learners.

Some examples of these strategies and frameworks include:

- SOLO taxonomy – is a means of classifying learning outcomes in terms of their complexity, enabling students and teachers to assess students’ work in terms of its quality not of how many bits of this and of that they have got right. For more information check out the resource site by NZ Educator, Pam Hook, and an example of use on TKI where NZ teacher Virginia Kung talks about how she applied SOLO taxonomy to her science lessons.

- “The learning pit” – from UK educator James Nottingham, the Learning Pit provides a way of understanding what happens when faced with a state of ‘cognitive conflict’ (i.e. when things get too difficult) and provides specific strategies to help resolve this. This is explained well in a video here from the students at Stonefields School.

- Inquiry approaches – there are a range of examples of inquiry approaches being used, with the common theme being the way they provide a scaffold for students to sequence and understand their own approach to learning based on the pursuit of an answer to a question or ‘wondering’ they have.

- Learn Create Share – Learn Create Share is a pedagogical approach based on an information processing model, developed and used by the Manaiakalani network. It is designd to put students at the centre of their learning providing a framework that is well understood by all involved, and supported by a rich array of tools and strategies for students to use.

- Portfolios – portfolios provide a rich and powerful way for learners to record their work, goals and achievements; reflect on their learning, and share and receive feedback on their learning. When learners are given control over managing their own portfolios they become more agentic and empowered in their learning.

- Project-based learning - is a teaching approach in which students gain knowledge and skills by working for an extended period of time to investigate and respond to an engaging and complex question, problem, or challenge. A good example is the Impact day at Albany Senior High School, which has become a model for many other schools to follow.

How might we respond?

Achieving the shift in ownership of learning is not easy within our current education system. While there are many examples of success at a classroom or individual school level, we are yet to see the impact at a system level. This is because our existing system is shaped to a large extent by (a) the policies that maintain a focus on schools, not students, (b) mindsets that are shaped by memories of the past and are not future-focused, and (c) structures that support the status quo, in particular things like ‘subjects’ in schools, examination processes and timetables.

To embrace some of the ideas around this trend in your own context, here are some ways of responding:

Personally

- Undertake a personal inquiry into some of the strategies/approaches outlined above, and evaluate what might be an appropriate thing to try in your context.

- Join a community of practice and/or follow some of the popular social media streams where other educators are discussing and sharing practice in these areas.

- Try something and follow a process of reflection and action as you develop you ideas and approach.

- Don’t forget to involve your students from the outset – specifically, use the continuum of student voice as a guide to deepen the way(s) you involve your students in this process.

As a school/cluster

- Form a professional learning group (or groups) to undertake a collaborative inquiry into some of the strategies/approaches outlined above, and evaluate what might be an appropriate thing to try in your context.

- Create a reading list and encourage staff to feed back on what they have been reading in this area (the resources list at the bottom of this section provides a start for some of the readings that may be appropriate here).

- Support the trialling of an approach or approaches, and ensure there is opportunity for regular reflection and review across the whole staff.

Involve the whole staff, students and community in a process of seeking their input into changes you are seeking to implement – use the continuum of voice as a guide to deepen the ways this occurs. - Use the Shifting the ownership of learning matrix as a guide for whole staff/cluster conversation to identify areas where changes could be made to increase student agency.

- Take time to review your school vision, mission and goals to consider how these reflect a commitment to shifting the ownership of learning in your context.

System

- Explore opportunities at a local, regional and national level to feed into initiatives (policy, resourcing, strategic) that will provide for and support greater levels of student ownership.