Schools as part of community

What's this all about?

For a long time schools / kura have been regarded as independent even ‘insular’ places where teaching and learning take place. We ‘send’ our tamariki to school or we ‘go’ to school to learn, in much the same way as we ‘go’ to our place of employment or ‘go’ to the dentist. This traditional view of schools and schooling has more often focused on the structures that support the institution, rather than activities that supports the learning.

Since the New Zealand education reforms of 1989 the policies and resourcing from central government have reinforced this notion of schools as stand-alone entities.

However, the idea of ‘self-contained’ schools is increasingly at odds with the growing ‘connectedness’ that characterises how we operate in so many other areas of our lives, particularly in a networked world.

If we consider schools and communities through an ecological framework, we can say that educators and learners are part of a learning ecology where boundaries are permeable. The concept of a learning ecology helps us to go beyond the narrow view of schools and other educational institutions as the sole providers of education for learners. Instead, a learning ecology takes into account the myriad of contexts, people and places encountered by a learner on her/his learning journey, both physical and virtual, and recognises that learning is transferred into and out of the school setting.

What's driving this change?

Key drivers for this trend include:

- focus on the learner

- investment in school facilities

- localised curriculum

- capacity of schools to provide breadth of curriculum.

Focus on the learner

While educators might argue a focus on individual learner achievement has always been at the heart of our system view, our record of success shows we still have a “long tail” of underachievement in New Zealand. The key thinking here is to address the inconsistency in the experience of so many learners as they progress from early years and through the schooling sector by providing a more ‘joined-up’ approach at all levels. When the education of a child is something the whole community takes responsibility for, the idea of competition between schools dissipates which causes a shift towards a a greater commitment to everyone collaborating in the interests of each learner.

Investment in school facilities

Providing public education costs money, and ensuring it is spent efficiently and effectively is a concern of any government. Efficiencies can be gained from sharing resources within and between schools, including staffing expertise, governance expertise as well as curriculum resources. This works in both directions. The local community will inevitably have more facilities, resources and expertise available within it than exists solely in centres and schools. Conversely, with the increasing demand for space and rising costs for land and buildings, centres and schools are becoming places of meeting for community groups and networking.

Localised curriculum

Community engagement is one of eight principles in The New Zealand Curriculum that provide a foundation for schools' decision making. The principle of community engagement calls for schools and teachers / kaiako to deliver a curriculum that is meaningful, relevant, and connected to students' / ākonga lives. Community engagement is also about establishing strong home-school partnerships where parents, whānau, and communities are involved in and support learning. This requires deliberate action to build relationships with community groups, and designing learning experiences with them that have impact in the community, for example, working together on community action projects such as planting in conservation areas.

Capacity of schools to provide breadth of curriculum

The traditional organisation of schools and centres as bureaucracies operating within hierarchical structures does not support or enable individuals and organisations to flourish. This is particularly evident when schools with finite resources struggle to provide programmes across the broad range of areas that learners may expect. But a shift is happening from an industrial/structural model to one that is organic/ecological. By extending the scope of access to expertise that supports learners in the areas they want to learn, schools better cater for students’ learning needs. They are also able to offer alternative pathways for the professional growth and development of teachers by enabling staff to build particular areas of expertise, and ensure a strong body of professionals in education.

What examples of this can I see?

The connections made between schools and community is a not new idea. Many schools have been operating successfully in this way for many years. The Community Engagement page on TKI provides examples of community engagement in New Zealand schools. These case studies illustrate how connections can be made with community, how communities can be empowered through the actions of local schools, and how schools can benefit from the contributions of community to the learning programmes they offer.

Further afield, the Schools as Community Hubs approach in Australia is showing positive results including improved attendance rates, parent engagement, and encouraging different ways to meet complex and changing needs of learners. The goal is to build a community where children, young people, teachers, parents, and community members work together interactively, recognising that children and young people learn best with real-life situations and hands-on activities.

A significant focus for New Zealand’s schools in this regard is an increased focus on the needs of Māori learners, with community connections being an excellent way of achieving greater levels of culturally responsive practice. This includes creating inclusive physical environments for students and whānau including design considerations that enhance building relationships between teachers and students as they work together in a variety of ways which best supports learning. Whānau and community are active within the school as important resources to learn from and with, in classrooms, kura and schools.

Increased opportunities to create connections both physically and in the online world, means schools need no longer work in isolation. The emphasis on schools working as clusters, highlighted in the Tomorrow’s Schools Review recommendations, illustrates this trend, as does the work of the Virtual Learning Network and other established clusters of schools through New Zealand. The benefits to individual learners, teachers and schools of being more connected to their communities are considerable as access to expertise and resources become available that no individual school could provide on its own.

An excellent international example of virtual community connectedness is the LRNG initiative in the US which works with cities and organisations to connect learning experiences to career opportunities. Their goal is to “close the equity gap by transforming how young people access and experience learning, especially those from underserved communities, and have inspiration and guidance to prepare them for life and work in the modern economy.”

UNESCO’s Learning Cities initiative is an example of community engagement on a significant scale. This project supports and improves the practice of lifelong learning in the world’s cities by promoting policy dialogue and peer learning among member cities; forging links; fostering partnerships; providing capacity development; and developing instruments to encourage and recognise progress made in building learning cities. The underlying belief here is that lifelong learning and the learning society have a vital role to play in empowering citizens and effecting a transition to sustainable societies.

How might we respond?

When considering how your centre or school might become better connected to the community/ies you are a part of, there are two perspectives to consider:

Looking out

- What community/iwi assets and resources could you be making greater use of?

- How might you involve learners in contributing to community projects that make a real impact on your community or local iwi?

- Who are the people and organisations in your community that could provide expertise in areas you currently can’t cater for within your kuru/centre/school? How might you best access this expertise?

- What connections do you have with other educational organisations in your community and are there opportunities to work together? Is there a mutual desire to provide the best educational experiences for learners in your community? Are you actively designing programmes and structures that make moving between and among your organisations straightforward for your learners?

- Which virtual communities are your students and staff connected to? How are these feeding into and informing the learning taking place in your centre/school? Are any of these purposefully designed to provide greater connectedness between learners and their whānau?

Looking within

- Curriculum: In what ways does the curriculum in your centre/school reflect a localised approach? Where could you be doing a better job of this?

- School and space design: Whether planning a new building or re-purposing existing spaces, ask whose interests are being served. Communities have specific needs which can change over time so providing flexibility to what the community needs is important. Remember, ‘Community develop spaces and spaces develop community’.

- Timetable: Can you use time more flexibly to allow meaningful access to and engagement with community resources and expertise?

-

Links

Ministry of Education | The New Zealand Curriculum Online | Community Engagement | Examples

South Australia Department for Education | Schools as community hubs

Explanation of their approach to foster schools as community hubs. The site has a excellent collection of showcase videos and case studies. It also has a Wellbeing for Learning and Life framework.

UNESCO | Institute for Lifelong Learning | UNESCO Global Network of Learning Cities

An explanation of UNESCO global network of learning cities to promote lifelong learning for all.

Ministry of Education | Educational Leaders | Embracing cultural narratives

LRNG - Learning redesigned fro the Connected Age

Learn how LRNG uses a platform to enable young people to access opportunities from their computer, smartphone, or tablet learning through online content such as playlists, gaming and badges.

NZ Virtual Learning Network Community (VLNZ)

Kia Eke Panuku | Culturally Responsive and Relational Pedagogy

This site includes a range of resources such as videos and focusing questions

-

Articles

-

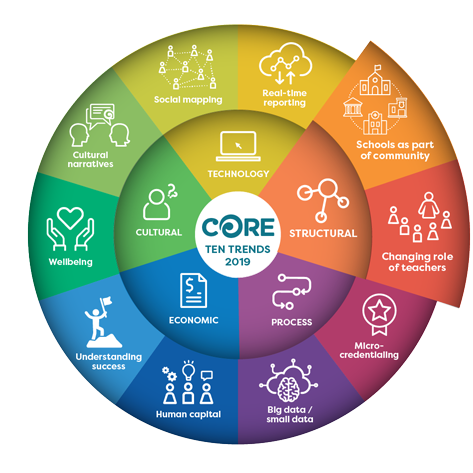

Ten Trends