Reflection: Article 2 and te reo Māori - 2018 to 2023

A reflection: 2018 vs 2023- what's changed?

2023, finally. The year teaching and learning Aotearoa New Zealand histories becomes compulsory. One of the very purposes of learning history is to look back, to glean insights from the past to make our present intelligible. Three years on from my previous reflections, I’m pausing to look back to consider what shifts might have been made to honour te reo Māori as a taonga.

The compulsory nature of the histories curriculum takes my thinking to the call to make learning te reo Māori also compulsory, at its very core the cry for rectification of significant loss. So what then has been happening? Top of the list for us in education is the impactful Te Ahu o te Reo Māori kaupapa. Te Ahu o te Reo has some of the country's most highly skilled kaiako reo Māori, who have poured reo Māori elixir into a famished nation, bringing understanding and cultural morality to those who stand before our tamariki. And it causes me to exhale, and express gratitude for this commitment – from the state and from kaiako, whānau and communities. Hearts have turned, a sincere commitment to correct pronunciation is becoming the norm, and each day more and more are seeing value in the language. I eagerly await the fruits of our consciousness.

As you read through the blog, consider reading through a history lens. As each year turns, how have we done better, what will it take to inspire change, and whose responsibility is it? It’s in the power of one, the power of the collective, and the power of now. Homai te waiora ki a tātou katoa. – Anahera, February 2023.

Treaty talks

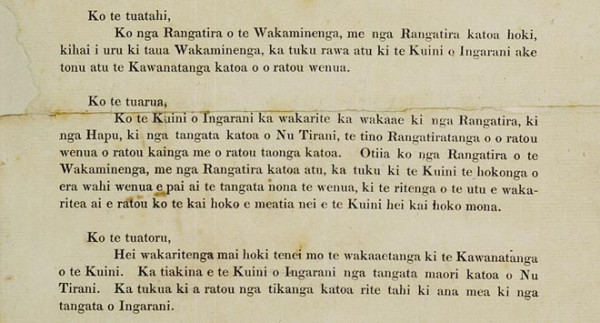

At the very heart of Te Tiriti o Waitangi, Article 2, we see mention of the word ‘taonga’. In the reo Māori version of the Treaty, the chiefs were confirmed and guaranteed the exercise of the chieftainship, or tino rangatiratanga over their lands, villages, and ‘taonga katoa’ — all treasured things. The crown also stated in the Treaty that there was to be exclusive and undisturbed possession of these treasures. Te reo Māori has, however, been disturbed drastically. On Waitangi Day this year, we remain in a state of fierce reclamation of our language. We continue to fight for this precious taonga that wasn’t duly protected and confirmed as intended under te Tiriti.

Te reo Māori is part of my absolute being. It flows like blood through my veins, it is in my spirit, it is in my soul. It is like oxygen, it heals, it makes my heart sing. It unites me with my tūpuna and, if I nurture it, it will connect me with my mokopuna. My reo is a huge part of my identity, possibly because I had to learn how to “be Māori”. Connection with te ao Māori was not a part of my upbringing. I started at the beginning and one step at a time have learned to walk and talk in the language and ways of my ancestors. It hasn’t always been easy, and, as I went through the stages of cultural reclamation, I learnt that attitudes towards te reo Māori are hugely diverse. I saw this diversity in my own family, my friends, and in fact everyone I interacted with.

In order to uncover the plethora of reasons why te reo Māori may or may not be embraced widely throughout our society, we need to dig deep into the ways in which the human heart responds to things Māori in general. Negativity towards te ao Māori is often felt, seen, and heard. This negativity is at times fueled by myth, media, intergenerational perspectives, or even perhaps from a space of divine, blissful ignorance. It often starts with the phrase, “I’m not racist, but….”. At the far end of the negativity scale, we see complaints received when a child is taught te reo Māori in the classroom or when parents fume because their children came home singing a Māori song. On a less explicit front, it is also felt when no attempt whatsoever is made to correctly pronounce Māori words. It is felt in the unseen, where monoculture is ever present.

As negativity continues to flourish, so does a cohort of society that is very pro-Māori. We see this in the uptake of those engaged in learning te reo Māori, in those who are committed to correct pronunciation, and those that encourage the use of reo in their everyday lives. There are also those that engage in kaupapa Māori, those that have relationships with Māori, and those that attend events in Māori settings such as marae. To all those that are taking any step, big or small, towards learning and using te reo Māori, thank you!

Of all the perspectives and attitudes towards te reo Māori, of particular interest is the notion of fear when faced with the idea of engaging with te ao Māori. Is this a fear of the unknown, fear of reprimand, fear of offending, or just fear of getting it wrong? When you learn te reo Māori you will and do get it wrong. It is like learning anything new — it is very difficult to master without practice. The only way through is through, and as with all the other learning challenges that life presents, te reo Māori is no exception to the rule. Sometimes fear may be a barrier — that, if we are honest, may actually be a handy excuse for not engaging in things that make us feel a bit uncomfortable.

If we were to exchange the word Māori, let’s say, for “maths”, what feelings does that invoke? Here are a few examples:

- “I don’t teach maths because I’m scared I’ll get it wrong”,

- “We only have 10% of children here who are interested in maths so we don’t really do very much”, or,

- “We do maths, for a week during our Matariki celebrations”.

Without a doubt, maths is an incredibly important life-long skill. How incredible could it also be to place importance on learning te reo Māori to transform not just one’s education, but to transform the very land that we live in. This is not meant to be a criticism for the sake of identifying things I don’t agree with, but it is a fight, it is advocacy, it is a plea — if our children are indeed the future, our conscious choices to do what is right for them and our society — to be free of racism, injustice, and inequity truly matters. And then there is the argument for correct pronunciation.

A focus on correct pronunciation may be painful or annoying to some. It may feel like a criticism, but imagine if everyone believed that 1 + 1 = 3. Some things are simply wrong. Like mispronunciation of te reo Māori. The language, then, just gets put into the old “too hard” basket. Or, is it even that pride may also play a part in our attitudes towards te reo Māori? I am not intending to come across as self-righteous; I am full of fault and my shortcomings are numerous. I am also full of love for, and despair over the current state of te reo Māori in our society. Advocacy for correct pronunciation is imperative, and even more so because the issue is never the issue. Underneath all the layers of mispronunciation is possibly a simple reason. It is this — ‘I actually don’t care’. I do not believe it is too hard. I do not believe it can’t be learnt. It is a conscious choice that each and every one of us makes every time we need to use a Māori word — will I attempt to say this or not? It is not about ability, but a decision made deep in the human heart.

Although discounted by many, I believe te reo Māori is currently in a state of vibrant recovery. Mainstream New Zealanders are turning towards our language now more than ever before in our history. The powerful model we see in Te Tiriti o Waitangi is one way we could actually work together to protect our taonga. I no longer see the Treaty as an object of negativity as I once did in my fiery youth. It now fills me with hope about a future filled with potential to restore te reo Māori as a taonga. Whenever I read the words of Article 2 they speak to me, reminding me of a time when we believed that language was a taonga. For the sake of a better future, let’s start today. A new word, committing to learning better pronunciation, an attitude shift or fulfilling your dream of fluency. Kia kaha rā ki a tātou katoa. He taonga te reo.

Explore more content

Explore our wide range of education related podcasts and blogs, ranging from experts discussing Kaupapa Māori, Cultural capability and te reo Māori, Leadership, Pacific viewpoints, Digital and innovation, Inclusive learning and more.