Communities of Learning | Kāhui Ako

What’s it about?

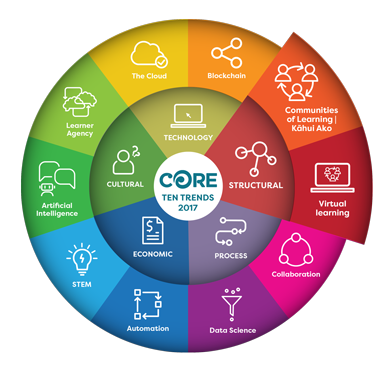

Communities of Learning | Kāhui Ako represent a new structural way of thinking about the New Zealand education system, placing the learner at the centre of design decisions, and connecting all the settings that make up their educational pathway. In addition, they enable the leveraging of resources, skills, and expertise that exist within individual schools, kura, and early years settings across the cluster, to better meet the needs of all learners.

Internationally, there is a move towards understanding organisations as entities that operate within networks. This is a part of an evolution in social organisation, considered by many as the ‘post-industrial’ way of operating.

Schools have operated for a long time within a bureaucracy that is largely hierarchical (industrial), where decisions are passed down through the structural layers of the system. New Zealand broke away from the highly-centralised view of this sort of system in 1989, when schools became autonomous, self-managing entities, but continued to operate within the mind-set of a hierarchy, both locally and nationally. A key characteristic of this was the increased level of competition between schools for both staff and students.

Becoming a networked community of learning involves understanding the principles upon which a network operates — as a series of nodes, linked by connections and relationships, kept active by the activity across these links designed to help the network grow and flourish. By implication, this requires schools to consider the focus of their activity (i.e., student learning) and to understand that they are but one of the many nodes in a complex series of relationships that contribute to a child’s learning over time.

Of course, networks on their own don’t change much. Thus, the structural change to a Community of Learning | Kāhui Ako by itself is unlikely to change much, especially for students. To realise the potential of these, school leaders, teachers, and communities must learn about and work to achieve the following:

- Learner at the centre – not as the ‘target’ to be served, but as an empowered, agentic individual with a voice. (See Learner agency)

- Distributed leadership – shifting the culture of schools from hierarchies to recognising that anyone at any level of the system can demonstrate leadership.

- Collaborative Inquiry – the engine of change – built on understanding that the solutions we seek exist within the network, and will emerge through working jointly to challenge thinking and practice. (See Collaboration)

- Knowledge building – being able to work with what is known (i.e. the knowledge from theory, research and best practice) and what the schools know (i.e. what the practitioners know) to create new knowledge (i.e. the new knowledge created through collaborative endeavour).

- Data driven decision making – knowing how to access and use data to make the decisions that matter for learners. This data will come from a range of sources, both inside and outside the school/cluster. (See Data Science)

To realise their potential, Communities of Learning | Kāhui Ako will need to provide additional value to the work of the individual settings that belong to them. This requires a strategic, purposeful, and focused approach to determine what the network can do that:

- is more effective and efficient than a single school, kura, or early childhood setting

- leverages the collaboration to extend and enhance the school/kura/ECE-based learning programmes, teacher practice and young people’s learning.

What’s driving this?

Like many system innovations, the Communities of Learning | Kāhui Ako development has several drivers, including:

Sociological driver

Recognising that hierarchies and bureaucracies no longer enable the flourishing of individuals and organisations in the modern world. The metaphor has shifted from an industrial/structural one to an ecological model.

Outcomes driver

While educators would argue a focus on individual learner achievement has always been at the heart of our system view, our record of success shows we still have a “long tail” of underachievement in New Zealand. The key thinking here is to address the ‘lumpiness’ in the experience of so many learners as they progress from early years through primary schooling and on to secondary, by providing a more ‘joined-up’ approach at all levels.

Economic driver

The provision of public education costs money, and ensuring this is spent efficiently and effectively is a concern of any government. There is a lot to be gained and efficiencies to be made from the sharing of resources within and between schools, including services, staffing, and governance expertise and curriculum resources.

Professional driver

Offering alternative pathways for professional growth and development to the traditional hierarchical positions – and thereby building a strong body of professionals who are leaders in classroom practice.

What examples of this can I see?

You don’t have to look far to see examples of networked communities of learning in the recent history of New Zealand education. Over the last forty years, the Ministry of Education has provided funds and/or resources, and levels of accountability for several different types of networks, each with a different purpose. All initiatives have focused on sharing what works and strengthening infrastructure to sustain new systems, processes, and practices. Over time, there has been the gradual shift in focus from schools and teachers to students and their learning, in what is now captured in the current strategy known as Communities of Learning | Kāhui Ako.

Key national initiatives were:

ICT PLD

Apart of the 1989 ICT strategy for schools was self-identified clusters of schools supported to collaboratively develop teachers’ ICT skills and capabilities.

Extending High Standards Across Schools (EHSAS) initiative

Groups of primary and/or secondary schools presented proposals for improving teacher practice and student achievement, particularly in literacy and numeracy, boys’ achievement, Māori achievement and developing the potential of gifted and talented children. Clusters were funded for the enactments of the proposals. Manaiakalani was initially an EHSAS project. It began in Tamaki, and now has outreach clusters in the Far North, Auckland, West Coast, and Christchurch. The focus remains on raising student achievement through supporting learners to be digital citizens and engaging families in the process. This initiative is now funded by the Manaiakalani Education Trust, drawing on resources from philanthropy, the New Zealand Government, and national and local businesses

Schooling Improvement Projects

Clusters of schools (generally based around pathways of primary to secondary schools) in regions that had high underachievement and high unemployment were supported to increase participation and engagement and accelerate progress (especially in reading, writing, and mathematics) by strengthening governance, management, leadership, and teaching. The Learning and Change Networks initiative followed, with an emphasis on teachers learning across and within clusters.

Virtual Learning Network Community (VLNC)

Regional clusters of schools are supported with an online space to host their learning exchange and to share resources, conversations, calendars, etcetera. Both teachers and students use the site. While this continues, there are now many more groups of teachers and leaders making most of the affordances of the online site for conversations and sharing resources.

How might we respond?

As an externally imposed model, the Communities of Learning | Kāhui Ako strategy has not been without its detractors – and many would argue for good reason. Aside from the politics of this, there remains, however, several very good reasons why schools should be exploring working more closely together in order to provide the very best educational service to learners.

Some questions to act as a stimulus with your colleagues include:

- What can our Community of Learning | Kāhui Ako do more effectively than a single school/early years setting?

- Are their particular community groups and organisations, for example, iwi and regional government, that we could engage with in a partnership to support our community vision for young people?

- Can we develop ways of describing, analysing, and responding to data and information that is consistent across our settings, so there is no doubling up of processes?

- How can our Community of Learning | Kāhui Ako leverage the collaboration to extend and enhance learning?

- Can we collectively describe what our young people are entitled to by critical transition points in their learning pathway, so we know what we are responsible for and what we are preparing learners for?

- Can we distribute leadership in ways that we can learn together?

- Can we be strategic in what we inquire into so that what we learn can be shared with others in our Community of Learning | Kāhui Ako?

-

Links

Investing in educational success

Investing in Educational Success (IES) is a government initiative aimed at lifting student achievement as well as offering new career opportunities for teachers and principals.

Communities of Learning | Kāhui Ako – Ministry of Education

The Ministry of Education portal for resources related to Communities of Learning.

Overview of the joint initiative

NZEI Te Riu Roa and the Ministry of Education jointly launched a new initiative to support children's success at every level of their learning.

Achievement challenges are shared goals that are identified and developed by a Community of Learning | Kāhui Ako based on the needs of its learners. The challenges are created by the Community of Learning and endorsed by the Minister of Education as part of the formation of the Community of Learning.

Infinity Learning Maps are a practical in-road into the science of learning-how-to-learn. The approach provides a tool for teachers to support students to draw a picture of how they see the interactions surrounding their learning.

Educational Positioning System

The Educational Positioning System offers a comprehensive process for formative school self-review to empower schools to shape and direct their future development.

The ICTPD School Cluster programmes in New Zealand are aimed at increasing teachers’ ICT skills and pedagogical understandings of ICTs, at increasing the use of ICTs for professional and administrative tasks in schools, and at increasing the frequency and quality of the use of ICTs in schools to support effective classroom teaching and learning.

The Learning and Change Network strategy (LCN) was developed to accelerate achievement for students yet to achieve national expectations for literacy and numeracy through future-focused learning environments. Learning and Change Networks involves networks of students, parents, teachers, and community members from multiple schools to collaborate in developing innovative new learning environments.

Manaiakalani Project – our schools

A cluster of 12 schools who share the vision to lead future focused learning in connected communities.

-

Articles

Communities of learners: what are the implications for leadership development?

Viviane Robinson describes the conditions required for CoLs to transform their member schools.

Communities of Learning | Kāhui Ako in action

This is the first of a series of iterative reports which draw together what ERO knows about CoL | Kāhui Ako, as they move from establishment to implementation. This report is based on information collected from schools (that are already members of a CoL | Kāhui Ako) during their regular ERO evaluations; information gained from the workshops ERO has conducted with CoL | Kāhui Ako and from the in-depth work we are doing alongside one CoL | Kāhui Ako

Communities of Learning | Kāhui Ako: Collaboration to Improve Learner Outcomes

This publication is designed to support Communities of Learning | Kāhui Ako by bringing together research findings about effective collaboration in education communities. It is supported by the publication Communities of Learning | Kāhui Ako: working towards collaborative practice.

Communities of Learning | Kāhui Ako: Working towards collaborative practice

An additional resource to Communities of Learning | Kāhui Ako: Collaboration to Improve Learner Outcomes. This resource is designed to support CoL | Kāhui Ako as they work towards effective collaborative practice. It is framed around key questions in each of the seven effective practice areas and is able to be used both as evidence-based progressions and as a useful internal evaluation tool.

Leadership for Communities of Learning (PDF, 700 KB)

This paper pulls together the intention of the Education Council of Aotearoa New Zealand with the five commissioned papers, issues raised by the commentators, and supporting literature.1 The Council will use the paper as a platform for discussion with stakeholders and to promote and influence the investment in, and the provision of, leadership development in New Zealand.

What works best in education: the politics of collaborative expertise (PDF, 520 KB)

The aim of this paper is to begin describing what a model of collaborative expertise would

look like and what is needed to get done to make it a reality.What doesn't work in education: the politics of distraction (PDF, 786 KB)

In this report John Hattie describes the confused jargon and narratives that distract us from the most ambitious and vital aim of schooling: for every student to gain at least a year’s growth for a year’s input.

Organising Schools for Improvement (PDF, 463 KB)

Research on Chicago school improvement indicates that improving elementary schools requires coherent, orchestrated action across five essential supports.

Inside-out and downside-up : how leading from the middle has the power to transform education systems (PDF, 1.5 MB)

In this paper Steve Munby and Michael Fullan start by commenting briefly on what we see as the inadequacies of the status quo; second, we propose a model of school collaboration which we feel has the potential to mitigate this issue; and third, we return to the bigger picture and in particular the role of the Leader in the Middle – the networked leader.

-

Research

Tribes, institutions, markets, networks: a framework about societal evolutions

This white paper was recently presented at a White House meeting on “Excellence in Education: The Importance of Academic Mindsets.” The meeting, held in mid-May, was co-hosted by the White House Office of Science and Technology Policy and the Department of Education and sponsored by the Raikes Foundation. The goal was to bring together a diversity of experts interested in academic mindsets.

Professional Capital as Accountability (PDF, 467 KB)

Santiago Rincon-Gallardo and Andy Hargreaves seek to clarify and spells out the responsibilities of policy makers to create the conditions for an effective accountability system that produces substantial improvements in student learning, strengthens the teaching profession, and provides transparency of results to the public.

The Nature of Learning : how can the learning sciences inform the design of 21st century learning environments? (PDF, 672 KB)

This booklet is a summary of The Nature of Learning, created to highlight the core messages and principles from the full report for practitioners, leaders, advisors, and policy-makers interested in improving the design of learning environments. The principles outlined serve as guides to inform everyday experiences in current classrooms, as well as future educational programmes and systems. This summary but for the full account and explanation please refer to the original publication.

-

Professional Learning

CORE professional learning solutions: Data-driven decision making

A deep understanding of relevant data involves exploring multiple perspectives of what’s going on within different conditions and interactions. Undertaking a number of purposeful interventions, designed to shed light on the challenge your community has set for itself, will be more successful than supposing a solution.

CORE professional learning solutions: Collaboration across sites of learning

Building a collaborative culture in and across your learning setting, with your community, represents a profound shift – from isolation and autonomy to de-privatised practice. We work with you, implementing structures and processes to support you as you build your collaborations and become a successful networked learning community.

CORE professional learning solutions: Strategic planning and evaluation

Decision making involves evaluation of what is happening, when it occurs and for whom. Scoping for the future, allocating and monitoring resources, delivers opportunity for a more equitable outcome and excellence for all.

CORE professional learning solutions: Strengthening capability

Often building capability can feel like a one-size-for-all approach. We recognise strengthening capability requires inquiry, with a strong focus on professional practices and social cohesion. The ultimate result sees teachers developing solutions together, using shared evidence and research.

-

Readings

Building and connecting learning communities: the power of networks for school improvement

Ideal for school leaders leading change efforts, this book describes how separate professional learning communities can be linked across schools by common instructional and learning issues to create dynamic networked learning communities.

The Learning Communities Online handbook

The handbook is intended as a reference for school leaders, BOTs and other parties to use, and has been designed to be incorporated into a folder into which supplementary resources and notes can be added.