Why this theme is important from an educational perspective

Educational institutions have become defined by structures that serve to support what they do and the ways they achieve this. This is particularly true in the compulsory sector. The concept of schools as physical places with rooms that accommodate classes based on age, who attend for fixed hours of the day to work through a curriculum based on the division of human knowledge into subjects, is an example of this kind of structure.

Many of these things are being questioned like never before, as education systems around the world struggle to identify what sort of responses are needed to an increasingly diverse and exponentially changing social paradigm.

To understand why the rethinking of the structural elements of our education system needs attention, it is important to recognise that many of these things were designed to address the needs of a society some 200 years ago. At that time our formal education system was developing as a priority for communities emerging from the agrarian to an industrial economy. Many of the structures that remain a part of how we operate today were inherited from the context of the time - masters responsible for passing on knowledge, bells used in factories to signal breaks, and the classification of subjects as a way of organising what needed to be transferred into the minds of young learners.

While these structural elements may have proved successful for a community of learners at a time where value was placed on conformity and compliance for a specific workforce, it is now recognised that the education system that has developed around them is not built for everyone. While it is completely true that all learners have the ability to succeed, many of them and their teachers feel alienated by the structures we have in place as a part of our education system. So, the very structures that support our system also fail many of our learners - making the need to address these concerns a matter of equity above everything else.

This is where the debates about structure often fail to address what is actually required. Consider the significant changes in the New Zealand education system in the past thirty years, with the Tomorrow’s Schools reforms of 1989 and the Review of Tomorrow’s Schools currently under way. In each case the focus of structural change is motivated more by economic efficiency than it is by equity.

If we consider the diverse backgrounds of learners who are now entering our education settings, and the increasing numbers from different cultural backgrounds and settings, we have a sense of how profound this issue is. A system and structures that are fundamentally designed around uniformity and standardisation will inevitably fail to provide the sort of settings in which diverse learners will thrive and succeed. Creating educational settings where learners feel they belong and can learn is key.

The rise of indigenous educational movements such as kōhanga reo and kura kaupapa Māori are a direct response and challenge to the structures and constraints of the well-established mainstream education system, which has consistently under delivered in terms of equity for Māori learners and their whānau. While evidence and data shows the success of Māori medium education, deep systemic and structural change is critical to ensuring authentic learning pathways for Māori learners and their whānau are well supported.

When considering our response to changing the structures in our system, our design must prioritise meeting the needs of all learners. We must be willing, as a system, to invest more in the areas that meet those needs.

Summary of the patterns and trends over the past 15 years

Over the past 15 years we have identified and commented on a range of areas that are indications of a system response to the structural changes that need to be addressed. This includes the changes to the physical structures (innovative learning environments), the design of curriculum, progress and achievement, and even the structure of the education workforce itself. Our organisational structures have also been changed by reshaping and transforming the ways in which our institutions operate, for example, leadership models, faculties, departments, syndicates, etc.

Across all of this we have had an increasing focus on shifting the orientation of learning to the learner and activating learner agency. This has put pressure on consideration of things like timetables, learning space design and curriculum design, for example, as the one-size-fits-all approach that requires conformity and compliance no longer meets the needs of a learner-centred paradigm.

At a whole-of-system level, the idea of having a nation of independently operating, autonomously governed, self-managing schools is another structure under pressure of change. During the past 15 years we’ve highlighted a number of changes that are moving us towards a more networked approach to educational provision, including the emergence of networked schools, the Communities of Learning (now Kāhui Ako) and ecologies of learning, that embrace a much stronger sense of the communities that schools and centres are a part of.

Another example of this shift is with the emergence of virtual/online education as both an alternative to the bricks and mortar learning settings, and also as an extension of what happens there, recognising the increasing role of online learning in our education system. Online learning is helping many education services to address the constraints of schools: as standalone places of learning, and provides opportunities to expose learners to a much broader and richer range of learning experiences and expertise.

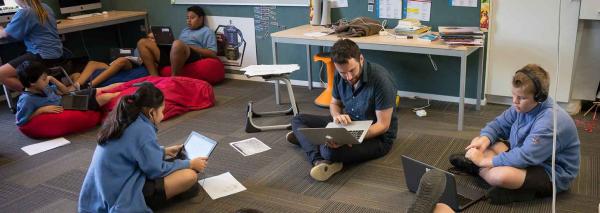

At a local level many education settings have experimented with moving from a structured day to more flexible arrangements with integrated learning experiences, ones that personalise learning where the design of learning is student-centric. These arrangements make use of a range of technologies to achieve this, enabling learners to continue their learning outside the constraints of the time and place of the traditional school day.

While there have been developments across a range of areas in the past 15 years, concerns about whether this progress is happening fast enough to ensure our education system remains fit for purpose in the 21st century continue to dominate the thinking of education leaders nationally and internationally - as this quote from a recent World Economic Forum publication highlights

These structures need to be people-centric and put learners right in the centre of learning, recognising the utmost importance of relationships, where diversity and the identity of all children and young people are valued

Examples of impact and consequences

Perhaps the most evident examples of the changes in the structural theme can be seen in what has been happening with learning spaces/environments. In the Aotearoa New Zealand context we’ve seen a significant focus on the building of new schools. This has been driven in part by rapid population growth in some areas, the remediation required for leaky buildings in others, and the impact of the Christchurch earthquakes in which many schools were severely damaged. The development of Modern/Innovative Learning Environments, now referred to as Quality Learning Environments by the Ministry of Education, has focused on the design of the physical spaces in which learning occurs, and ensuring these are informed by and matched to the pedagogical practices taking place within them. The emergence of more open and flexible learning space design is a feature of this thinking. The concept of learning spaces extends beyond the traditional bounds of learning centres to include what is happening in public libraries and marae around the country, for example.

The growing dissatisfaction, in some quarters, with the performance of state schools and their inability to change their structures to meet the needs of our changing communities led to the development of some alternative approaches by the National/ACT government. This includes the introduction of charter schools, which were intended to create more freedom for educators and communities to explore innovative approaches to schooling. The introduction of public-private partnerships (PPP) for the building of new schools was another alternative approach, designed to help increase the capacity of the government to keep up with the demand for new school builds. While neither of these approaches are supported by the current Labour government, concerns remain about how we can accelerate the required changes to the structures of our education system, to make them fit for purpose, and affordable, into the future.

An area of thought that is gaining momentum across all areas of government thinking, both nationally and internationally, is the idea that education/learning must be thought of as more than what happens in physical locations, such as: early childhood centres, schools and kura. As a consequence, we’ve seen an emerging push for strong partnerships to be built between education settings and their communities. This includes, for example, using a range of strategies for engaging parents and whānau, including using portfolios, two-way home-school interactions, and opportunities for connecting learning in in the education setting with what is happening in the community through community-based, social action projects. A more specific example is engaging whānau through Māori graduation, where the development of Māori graduation ceremonies has led to deeper community connections and growing pride in student achievement.

The idea of becoming more connected and networked applies not only to settings connecting with their communities, but also with others. The growing emphasis on the development of Communities of Learning and Kāhui Ako illustrates this, with changing roles for teachers and leaders that focus on the collective impact of schools and centres on meeting the needs of a learner through their learning life.

As the boundaries between learning settings, and between them and their communities, have become blurred in these ways, the growth of virtual/online learning has enabled even greater opportunities for this sort of networking and connectedness to occur. The contribution of groups such as NetNZ which provide learners in remote or rural secondary schools with access to the subjects of their choice, while being able to remain in their local school, is a good example of this. So too is the VLN-Primary, which offers a range of learning experiences in areas such as second language learning, that may not be provided in the local primary school setting, and allows learners to access specialist knowledge and support from wherever and whenever they need it.

What might we see moving forward into the future?

It is clearly evident that many of the industrial-aged structures upon which our current education system depends are no longer fit for purpose. Despite the voices of many within the profession and in our communities who wish to see them remain, there is an urgent need for more informed debate and decision making, as we seek to create a system that is empowering of all learners. We cannot continue with structures that privilege some, while alienating others and making it more difficult for them to succeed. The issue of systemic inequity cannot be addressed without taking a critical look at the very structures that are contributing to that inequity in the first place.

Further, we must recognise that the structures within which we operate actually reinforce the beliefs that underpin them, and that these in turn shape the behaviour and beliefs of those affected by them. If we are determined to ensure that our education system succeeds in developing young minds capable and willing to help shape future societies, to address the uncertainties that will be faced, it is crucial that we radically rethink the very aim of education. Structures need to be people-centric and put learners right in the centre of learning, recognising the utmost importance of relationships, where diversity and the identity of all children and young people are valued. This in turn will foster learning environments where cooperation, empathy, social awareness and global citizenship are at the forefront of teaching and learning.

Perhaps the most significant structural changes we will see into the future will be as a result of three drivers:

- A focus on the learner and whānau. While we claim that this has been a focus of our system over the past few years, this is not yet the experience of all learners, or of all whānau. Many of the structures that support our system are biased towards the one-size-fits-all approach of the past, and privilege a few over the many. We must see an increased emphasis on engaging with learners, families and whānau in authentic ways that lead to the design of structures that truly support everyone being able to experience success as learners.

- Redefining curriculum and assessment. The structures that currently dominate our understanding of what is taught and how it is assessed must be challenged across our whole system. There is almost universal agreement among educators and the wider community, including employers, that a competency-based education is essential as we prepare our young people for the future. Such education promotes qualities like cooperation, curiosity, courage, compassion, emotional intelligence and adaptability. Despite this agreement, the model that dominates so much of the learning activity in our educational settings is characterised by a focus on content, influenced to a large extent by assessment structures. The need to redefine success is a critical part of this driver. We need to look more widely than the traditional ways of measuring success, which typically examine content knowledge and skill as measures of academic performance.

- Expanding the concept of school. In future years we will continue to see the notion of the independent, autonomous entity of a school be challenged from two directions as we've seen most recently in the temporary closure of all learning settings across Aotearoa during the Covid-19 pandemic. Firstly, the physical and metaphorical walls separating a school from its community will become more permeable, with greater community engagement, more networking among and between schools, and the emergence of learning ecosystems that support learners in a variety of settings. Secondly, the impact on online/virtual learning will move to becoming part of the mainstream way in which educational opportunities are provided. This will no longer be the second choice option, and no longer operate outside of the frameworks of educational policy and resourcing.

-

Consider

Some questions that may help guide your thinking and discussions within your education setting at a strategic level are:

- To what extent, and in what ways are you engaging meaningfully with your learners and/or their family or whānau to genuinely understand their identity and background? How are you understanding what makes them feel they are heard, listened to and their ideas are acted on with a sense of belonging as part of decision-making about the structures (e.g. timetable, curriculum, learning space design) that define the operation of your education setting?

- In what ways does your educational setting help learners to understand what success looks like and means for them, particularly beyond traditional grades?

- How might you, as a staff and with your community, work to better understand that addressing issues around structure are critical to achieving greater equity in our education ecosystem and in your setting?

- What are the key drivers behind decisions made in your setting around curriculum (e.g. subjects taught), use of time, allocation of tasks to teachers, design and use of learning spaces, etc.? Can you honestly say that these decisions are made in the best interests of your learners, informed by their educational, cultural and social/emotional needs? What evidence do you have to support this? What voices/considerations are missing?

- What opportunities are you taking to build greater relationships with others outside of your setting, including community and other educational settings? Is the vision of ensuring support for learners throughout their learning pathway a key driver for this? What evidence could you provide to support your view?

- How might greater use of virtual/online learning ensure all learners are able to access the learning opportunities they need and deserve? How might this create new opportunities for your staff and community, also? Is your consideration of this tempered by the perception that it is a second choice or last chance alternative to face to face teaching, or do you have a vision of how this might be used in a complementary way to create even richer and broader learning experiences for learners?

-

Resources

For those wanting to dig deeper into some of the key drivers in this area, some references worth checking out include:

From CORE

- Modern learning environments

- Re-thinking learning spaces from a deep learning perspective

- Designing new buildings for NPDL

- EDtalks videos - Hana O’Regan and Anne Milne

From Te Kete Ipurangi (TKI)

- Technologies - Quality Learning Environments

- Quality Learning Environments

- Engaging with the Community

- Leadership in Communities of Learning

- Professional Learning Communities

- Leading Local Curriculum

- Flipped Learning

From Grow Waitaha

Māori Education

- Māori Education - Briefing for Incoming Minister

- Kaupapa Māori Educational Initiatives - Professor Linda Tuhiwai Smith

Inclusive Education

- Planning inclusive learning environments

- Activating critical theories

- The Lundy model of child participation

- Rights: Now! Engaging with children on matters that affect them - Office of the Children’s Commissioner

Ministry of Education

-

Examples in practice