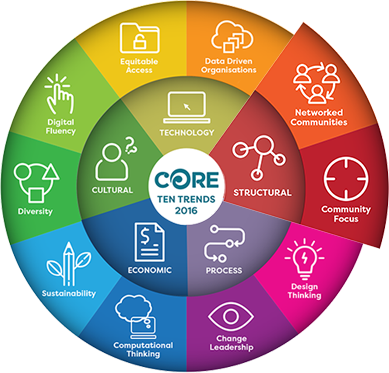

Networked communities

Over the course of recent history we have seen many examples of collaboration and networking. It is a trend that has ebbed and flowed according to our perceived and real needs for connectedness, whether they be economic, socio-cultural, practical, spiritual or a myriad of other drivers.

Now, with worldwide connectivity made effortless by technologies we are starting to see a breaking down of hierarchies. People now view knowledge as contestable and in many cases as privileging some, rather than all. Alongside this trend is the emergence of what Rayner (2006) refers to as “Wicked Problems”. These include a long list of wellknown problems such as climate change, educational underperformance, persistent poverty and biodiversity loss that:

- can’t be addressed using simple problem solving

- can only be addressed with “clumsy” solutions by bringing together disparate perspectives on the problem in ways that all voices are heard and responded to (Rayner, 2006; Verweij et al, 2006 in Bolstad, 2011).

The 2013 OECD report (PDF, 815 KB) on entrepreneurial ecosystems and growth oriented entrepreneurship makes the distinction between traditional policies with a focus on individuals and geographic clusters, and growth-orientated policies with a focus on networks of entrepreneurs and temporary clusters.

This represents a shift from hierarchies and distinct organisations towards networked components in an ecosystem who work together to solve our complex problems. It requires us to shift from working in organisations where people build knowledge and become more empowered in collaborative local groups, towards networked communities where the collaborative groups are looking to network beyond their local boundaries to include multiple perspectives in order to solve complex problems. These Networked Communities are sometimes described as emerging Horizontal Connections to allude to the fact that we are shifting away from hierarchical structures that can be rigid and that often don’t allow for genuine equitable cross-pollination of ideas and solutions.

Implications for education

In New Zealand we can see this trend emerging through the Investing in Educational Success Policy which includes support from the government for Communities of Learners. As more and more schools and services become part of Communities of Learners, we need to consider a shift beyond the sharing level and into true collaboration where we consider the challenges that we need to solve together and create deep-rooted, community-based visions to be achieved over time.

In past collaboration efforts in Aotearoa there are examples of effective practice that include schools and services working together to build a strong vision that is relevant to all involved. These groups have also used other effective approaches such as building a deep understanding and use of everyone’s needs and strengths using some kind of self-review like Teaching as Inquiry. They have developed effective relationships with each other at all levels from leadership to learner and each community member knows their role in achieving the vision. This allows them to challenge and critique each other in ways that ensure that the community grows its capacity.

The challenges in developing such a strong, collaborative, vision-based community is that people tend to build walls around the community that are not permeable. When people find something worthwhile and important that they can relate to and find inspiration in, the temptation is to protect the community from “outsiders”.

Questions to consider

As we begin to think more and more about Networked Communities, and the need to solve complex problems, we will start to think more about how we contribute to the social capital of the communities around us and we will start to consider the following questions:

- How permeable are the boundaries around our communities? Should we have boundaries at all if we want to encourage engagement with multiple perspectives to solve our complex problems?

- How can communities put learners in the driving seat, giving them the chance to socially construct knowledge with each other and adults, and encouraging them to contest existing knowledge?

- Is the fact that many humans were forced into factory model educations for the industrial age impacting on the way we develop our collaborative communities? What assembly line practices can we get rid of to make room for new and innovative solutions?

- What can we learn from the many indigenous cultures who continued to thrive in intergenerational, whānau-based, holistic learning that would prepare them for a future that valued people over industry? - something that we need now more than ever. How do our collaborative communities invite and approach local iwi to be part of vision development and achievement? How might we show interest in and support iwi initiatives?

- How can we move from being collaborative communities to networked communities? How will we know when we have succeeded in this?

- To be a networked community do we first need to be networked organisations? (Core Education website)

Links

The 7 Principles of Learning to support learning that is actively constructed through social negotiation (PDF, 672 KB)

Ministry of Make at Taupaki School: Make, Create, Share through connections with the community

On the Edge: Shifting Teachers’ Paradigms for the Future (PDF, 274 KB)

Collaboration resources for building a community of schools and services (and beyond)

Innovate Change - bringing together health and social care programme services

MOE Guides for IES Communities of Schools (PDF, 287 KB)