Changing role of teachers

What’s this all about?

Teachers work in increasingly complex and diverse settings and they have very different and changing professional learning needs.

(Kay Livingston (2017) The complexity of learning and teaching: challenges for teacher education, European Journal of Teacher Education, 40:2, 141-143, DOI: 10.1080/02619768.2017.1296535)

At the heart of redesigning our education system is a dramatic need for schools / kura and teachers / kaiako to prepare our students / ākonga for a future characterised by change and uncertainty on a scale not previously experienced. This shift requires us to redefine the core business of schools and the role of teachers within them.

In New Zealand, and other nations, this shift is marked by a move from a “one-size-fits-all” approach of delivering and receiving knowledge, to an approach that honours the individual and their diversity. While considerable effort has been spent identifying and describing a changing model for learners, what does this mean for the core role of the teacher?

A traditional view of the teacher’s role is as a giver of knowledge. Teachers share knowledge with students on a particular subject, through lessons that build on their prior knowledge and moves them toward a deeper understanding of the subject. Supporting this view are underpinning beliefs about knowledge as being ‘fixed’ and able to be ‘transferred’.

Of course, teachers do have other roles: as evaluators of how effectively the transfer of knowledge has been achieved, as managers of behaviour and expectations, and as ‘carers’ catering for the health and wellbeing needs of those in their charge. But for the most part these exist to ensure the process of knowledge transfer is efficiently served.

Today these expectations are being challenged. The fundamental premise of teachers as the ‘conduit of knowledge’ is no longer valid. In recent years cliches such as “moving from sage on the stage to guide on the side” have emerged to illustrate the awareness of the changes that are happening, focusing on the role of the teacher as more of a facilitator, guide, mentor and coach for example. This is an important part of the current issue, but it needs to go deeper than that.

Working in school communities that are very diverse increases the responsibility for leaders and teachers to protect and enhance the language, customs and cultural identity of the community and country that they reside in. For example, it is vital that teachers protect and revitalise the duel heritage of both the European and Māori cultures by actively, and equitably, incorporating both in teaching and learning programmes. Teachers have an important responsibility to know the cultural identity of their students, especially Māori students here in New Zealand, so that we can understand how they learn best and personalise the learning to match their cultural background and context.

As teachers move beyond their traditional role as experts in pedagogy and curriculum, the expectations placed on individuals are becoming unrealistic and unsustainable. Teachers are now expected to meet the social and emotional needs of a diverse learner population, rapidly implement ever-evolving pedagogical practices, deal with major structural changes in learning environments, and do all of this more collaboratively.

Added advances in technology mean that many of the the ‘instructional’ roles of teachers are being challenged by personalised online learning services, chatbots and artificial intelligence, to the point that some are questioning whether there is a future for teachers as we know them. As aspects of the teaching role become more automated teachers must have a stronger emphasis on building capabilities across the key competencies such as as collaboration, communication, critical thinking, and the ability to problem solve and make quick decisions. In addition, the practice of working in isolation with a particular cohort of learners must shift to a more team-based approach, not only within the school environment, but recognising that the education of a young person is the responsibility of community as a whole.

What’s driving this change?

There are a number of key drivers of this change, including:

A change in the ‘why’ of education

As evidenced by:

- Shifting from the concept of ‘delivering learning’ to ‘enabling learning to happen’.

- Ensuring the school community provides learning experiences that foster positive emotion to enhance greater cognitive development.

- Learning experiences designed to meet the diverse and variable needs of all learners to ensure learning is fully inclusive and promotes success for all regardless of ability.

- Increasing recognition of societal changes, including issues of equity and catering for students who come to school disadvantaged.

- Pedagogies that focus on engagement, inquiry and active, flexible, deep learning.

- Collaborative practice and the need to build relational trust across teams.

- Deliberately designing learning to have horizontal connectedness across a wide range of curriculum areas, the community and the wider world.

- Learning experiences that open up opportunities for students to be curious, creative, and innovative.

- Deliberately designing learning for innovation and creativity.

- Designing learning experiences where students can develop social skills and relationships, collaborating with a range of different people and peers.

Technology changing the nature of human capability and capacity

As evidenced by:

- The unpredictability of the future workforce and rapid advancements of automation. The jobs of today were not the jobs of 10 years ago and will be not the jobs of 2030.

- The different skill sets and attributes needed to contribute to society with demands for innovation, creativity and sustainable practices that have minimal impact on our planet.

- The emergence of robotics and artificial intelligence (AI) on such a scale that the demand for humans as teachers/workers may actually be under threat.

Change in concept of knowledge

As evidenced by:

- Thinking more of knowledge as a set of cognitive strategies than as as a ‘thing’ or as the goal of learning.

- The exponential rate of change leading to rapid knowledge obsolescence and rapid knowledge emergence.

- An economy that succeeds through the deployment of knowledge.

- Changes to the foundation of knowledge-generation, from being the domain of academia to recognising the importance of peer-based knowledge, community knowledge and cultural knowledge.

Shifts in the ownership of learning

As evidenced by:

- Increased learner agency with learners also being teachers within the environment.

- Increased emphasis on learner-centred approaches, including self-directed, self-determined and self-managed learning.

- Increased emphasis on the importance and acknowledgment of student voice and open opportunities for expressive outcomes.

- Development of learning environments suited to collaborative practices.

Increased focus on culturally responsive practice

As evidenced by:

- Recognition of local languages, cultural practices and history with in the national and local curriculum.

- Prioritising bicultural perspectives over a dominant culture discourse.

- Valuing place-based knowledge and history (the cultural narrative).

- Using both indigenous and western epistemologies, research methodologies and ways of learning.

- Deliberate provision of opportunities for students to strengthen their own connection to their language, culture and identity which will in turn support teachers to respond to their learning needs.

- Engaging students with learning in, through and about their own culture, as well as the culture(s) of the country they reside in.

What examples of this can I see?

The shift to innovative learning environments (ILEs) that make greater use of open space, and encourage collaborative pedagogical practices is evident across all levels of the system. While not all agree with this move, it certainly reflects a similar trend in workplaces where companies seek to achieve similar lifts in performance and productivity as they address the challenge of a constantly changing work environment. Teachers working ILEs need to learn different ways of interacting more closely with peers, and with a wider range of students. This calls for adopting different roles from when they worked alone, having their own classroom with their own students.

See for example:

- Wairakei School’s “Learn it Prove it” approach

- Ten Innovative strategies for innovative learning - TeachThought

- Transform curriculum and teaching practice - Dr Wendy Kofoed

The economic drivers of education require consideration of the future workforce, especially those brought about by rapid advancement in technology and the increased use of automation, including the use of robots and AI. Teachers must be prepared to focus on developing capabilities such as resilience in young people to cope with the immense change they will experience, and less on the specific content to be delivered in the curriculum.

See for example:

- Technology, jobs and the future of work - Forbes

- Preparing today’s students for tomorrow’s world - Government of New South Wales

The work of teachers itself does not escape this threat, with the increase of intelligent tutoring systems and AI-supported training systems providing high quality, personalised learning for students already. Virtual assistants, chatbots and e-learning platforms are beginning to lead to more adaptive, personalised learning for students. This is likely to have a bigger impact in future as bots and personal assistants that use AI and natural language become embedded and ubiquitous.

See for example:

- Why robots could replace teachers as soon as 2027 - World Economic Forum

- Should technology replace teachers? - William Zhou | TEDxKitchenerED

With the change in how we think about knowledge comes the need to think very differently about how we think about curriculum, and the role of the teacher. More than before, the emphasis on inquiry-based learning and pedagogical approaches such as constructivism and constructionism will need to prevail, allowing for authentic, student-led, knowledge-construction activities to be the way the curriculum is led.

See for example:

- Leading Curriculum Innovation in Practice

- Building cultural knowledge - Educational Leaders

The shifts in ownership of learning being experienced in a range of learning environments at all levels, requires the most significant and intentional change in teacher role. While the role of instructor will continue to feature for a part of the time, a broader range of strategies will be required. Building the capability of students to self-manage their learning is vital here, with questions such as: What do I need to learn? Why is this important for my learning? How will I learn this? How will I know when I have learned this?

See for example:

How might we respond?

So what are the new roles and responsibilities of teachers as we shift the ownership to the learner and personalise learning experiences? How do we make these significant changes to a more learner-centred and learner-driven paradigm?

Some questions to help you think about the next steps:

- Consider the case for change laid out in this trend, what do you agree with? What do you disagree with? How would you describe the key attributes required by teachers to meet the needs of our students, now and into their futures?

- Why is the idea of personalisation appealing for your students, your faculty, your school? What is your vision for personalisation?

- What examples of this change in role are already evident in your context? How might these become common features of how teaching and learning occurs?

- What things might you have to ‘let go’ in order to effectively make some of these changes?

- Where might you start, personally and collectively?

- What are the consequences for your students of NOT responding? What might the impact on their learning and their futures be?

- If you are appointing new teachers what are the attributes you are looking for?

-

Links

Tech’s role in learner-centred education - Executive Director of Education

The right technology tools can help pave the way for a new style of learning that empowers students.

-

Articles

This article is set out with a range of deep questions that focus on personalised learning.

An interesting article that explains the coming waves of automation that will shape the global economy and how New Zealand is positioned to manage these changes in the workforce.

PWC Full Report | How will automation impact jobs?

Analysis of the waves and impact of automation An analysis that explores the economic benefits and potential challenges of automation. A section on education and retraining critical to adapting to new technologies outlines some key teaching and learning focus areas.

United Nations Sustainable Development Goals | About the Sustainable Development Goals

The United Nations have set out 17 development goals as a blueprint to achieve a better and more sustainable future for all. A great resource that could drive learning for your students. You can click on each goal which will you give you extra information, facts and figures and links.

-

Research

A comprehensive report which explores current research, innovative pedagogical approaches, frameworks, examples and experiences from a network of schools towards innovative pedagogies.

-

Readings

OECD | Innovative Learning Environments Project | The Nature Of Learning

Page 4 explains the gatekeepers to guide any learning: emotion and motivation.

-

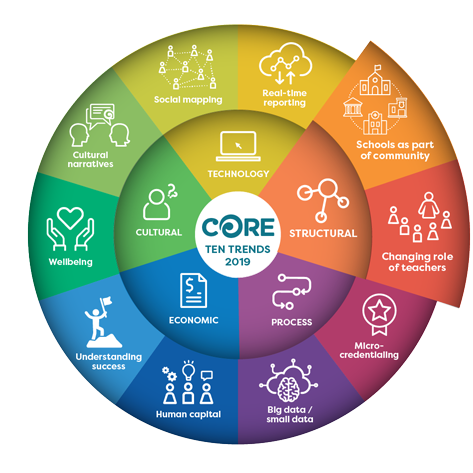

Ten Trends

-

Videos

CORE Edtalks | Culturally located spaces for Māori students

Janelle Riki-Waaka, CORE Education, discusses how Māori students have an opportunity to be future leaders in our schools particularly in environments that are embracing future-focused, innovative practices to cater for the needs of millennium learners.

CORE Edtalks | Giving mana to Tiriti o Waitangi in our schools

Janelle Riki-Waaka, CORE Education, discusses how focusing on what it means to be a school unique to Aotearoa New Zealand and reflecting our bicultural heritage gives mana to Tiriti o Waitangi. Janelle encourages educators to ask themselves: How would I know I am in a school in Aotearoa?

Mana: The power in knowing who you are | Tame Iti | TEDxAuckland

Tedx Talk by Tame Iti exploring the old saying "Te ka nohi ki te ka nohi". Dealing with it eye to eye creating a far more productive space for open dialogue around any issue.

Why cultural diversity matters | Michael Gavin | TEDxCSU

Michael Gavin, associate professor of human dimensions of natural resources researches biological diversity, discusses the importance that history, language and tradition have in the preservation of culture.

Ann Milne; Colouring in the White Spaces: Reclaiming Cultural Identity in Whitestream Schools

Dr Ann Milne speaks at CORE Education uLearn 17 conference in Hamilton. She asks us to think about what community and collaboration look like for the learners our system marginalises and minoritises.